Joseph Barkhurst was a prominent Otoe county farmer who studied dry-farming. As a new farming method, dry-farming meant to break the soil, then cultivate it, and after that, dragging and harrowing versus repeated breaking. This is the system of cultivation – one part of the land is left without cultivation or breaking for one year and another part is cultivated, and the land is rotated in that way. Mr. Barkhurst purchased 320 acres near Alliance and utilizing dry-farming methods developed a remarkably productive farm.

THE FIRST SUCCESSFUL DRY-FARMER ON THE BOX BUTTE TABLE

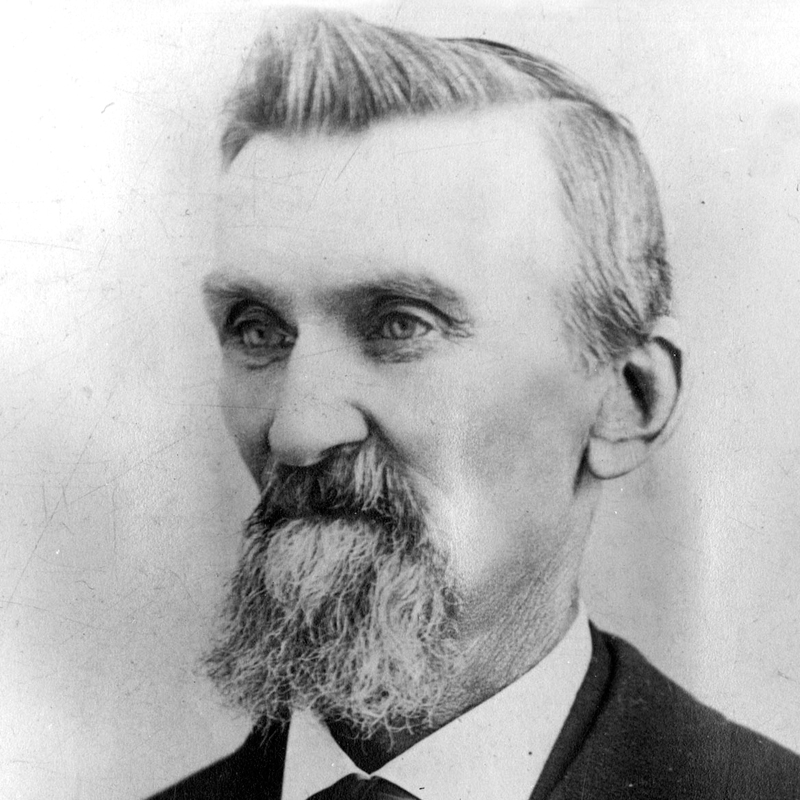

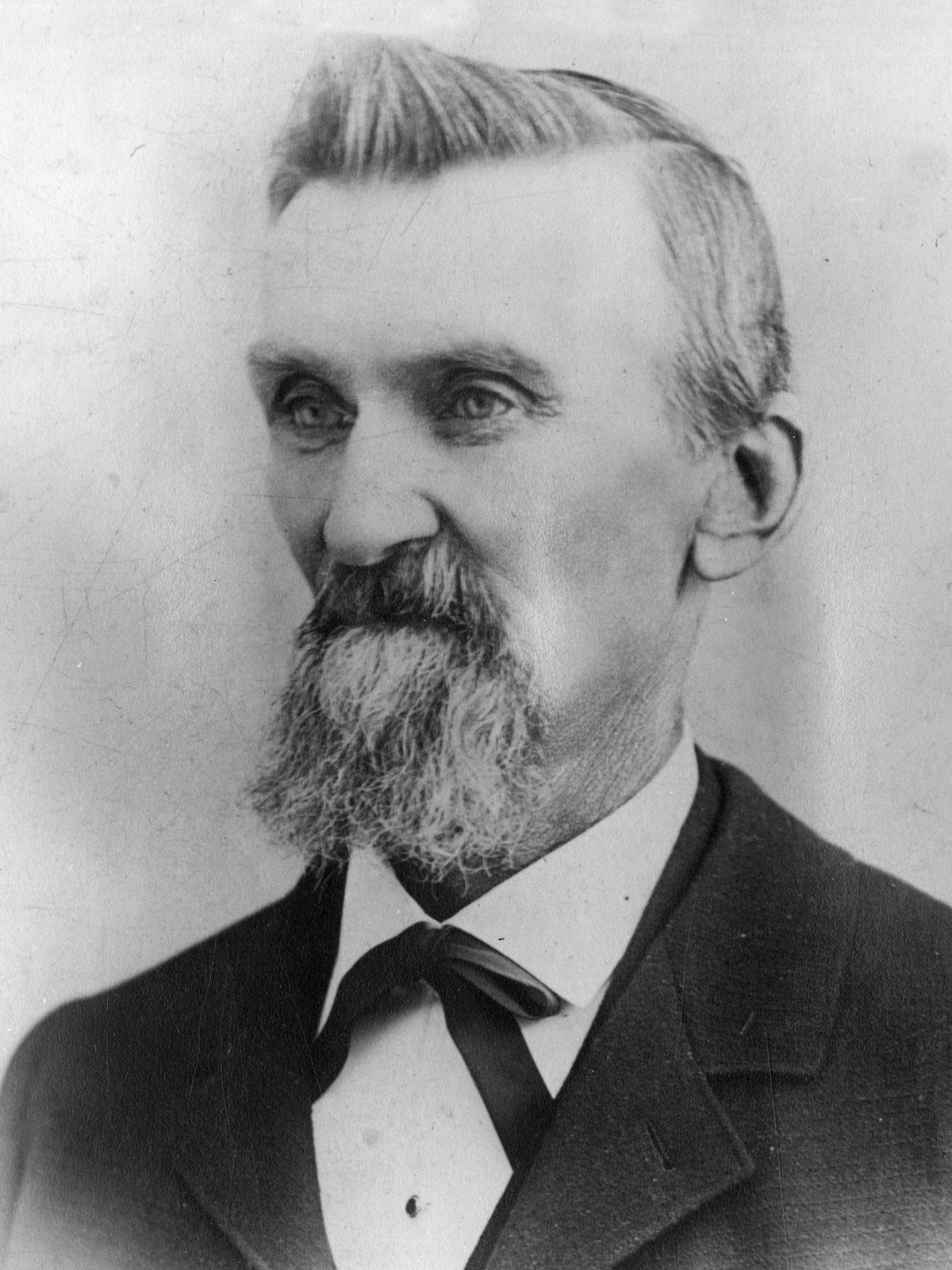

Joseph Barkhurst

- - By Representative F.M. Broome.

Delivered Jan. 4, 1923

Dale P. Stough

Reporter.

Copy of original

Oct. 27, 1926.

THE FIRST SUCCESSFUL DRY-FARMER

ON THE BOX BUTTE TABLE.

- - By Representative F.M. Broome

Gentlemen: - You will just listen a few minutes and I will promise that I will not tire you or extend my remarks unduly. I will just address a few facts.

This dry-farming is a matter about which there has been little study, beyond the western or northwestern part of Nebraska. I anticipate that all of you are familiar with the conditions existing in what is commonly called the sand hills of Nebraska. I will say that there are but few dry-farmers there, as conditions exist. It is true that some of you perhaps, have superficial idea of that country out there. Very few have a positive idea of it.

Box Butte County is in the western part of Nebraska. But a very small portion of that county is embraced in what I will refer to as the Box Butte table – perhaps a portion of some thirty by thirty-six miles. Box Butte County is surrounded on the north and west by the Pine Ridge, on the south and east by the well-known sand hills. We will not confuse the sand hill territory with the Box Butte Table, because the Box Butte table is a distinct territory by itself. The sub-soil is such that it cannot be farmed by eastern methods.

As early as 1884, before the railroad extended beyond Broken Bow, the settlers began to come in by the way of Hay Springs and Chadron on the Northwestern Railroad. Most of the settlers came in 1885. These settlers came largely from eastern Nebraska, Iowa, and Illinois, and they brought their ideas of farming with them. Their idea was to break the soil in the spring, seed it and break it again the next spring. That was the form of breaking to which they had been accustomed, but it was not so applicable to the sand hills. They did not realize that, coming into the sand hills, they should use a different method of farming. For awhile their methods succeeded fairly well, for during the seasons of 1885, 1886, 1887 and 1888, there was an abundance of rain, and they farmed and broke the land in the same way as they had been doing further east. The fall of 1888 was the high tide for Box Butte County, for at that time the county received two premiums at the state fair in Lincoln.

In the fall season of 1889 came the drought, and crops were a failure. In 1890 crops were again a failure and the country kept getting worse. It was then there came up this agitation for what might be called dry-farming. During the period of drought that began in 1890 there were a number of different ideas advanced. Some gentlemen came out with scientific ideas; reasoned why the drought had afflicted the country and argued that it was because they had not broken the soil properly. The first idea was to put on six horses in breaking and turn the soil up three or four feet deep, but in that country the more the soil was turned, the dryer it became – in fact, it baked.

About that time there was considerable agitation over this subject. I think there was an article published in the Nebraska Farmer, and the Omaha Bee also had a prominent part in it.

There was a gentleman farming down in Otoe county by the name of Joseph Barkhurst. He was quite a prominent farmer there, a man of advanced ideas who had studied this dry-farming program. He came out there where Alliance now stands, bought a place four miles northwest of there of 320 acres, and proceeded on this theory of dry-farming. Dry-farming does not mean continuous breaking, nor does it mean deep breaking. It means first breaking the soil and then cultivating it, and after that, very little breaking, but dragging and harrowing. This is the system of cultivation – one part of the land is left without cultivation or breaking for one year and another part is cultivated, and the land is rotated in that way.

Mr. Barkhurst tried this system in 1890. He said, “I am going to grow trees on something like fifteen acres.” He broke out that space and planted shade trees. I have forgotten the different kinds, but they were mostly box elder and some other varieties of trees. For three years not a drop of rain fell there. All of that time he worked the soil on that principle, breaking it shallow, dragging it and harrowing it. Those trees grew from little seedlings in 1890, when he first went on that farm, until somewhere along about 1897, by which time he had a remarkably good farm. The trees by then covered over the fifteen acres, some of them had grown to a height of fifteen or twenty feet, and they were flourishing. His entire farm of 320 acres had been broken up and cultivated by those methods.

In 1897, Mr. Henry W. Campbell, the father of this dry-farming system, came up there. He came to see me when he first arrived in Alliance. I knew of Mr. Barkhurst’s successful venture and was able to refer him to this dry-farming enterprise. I took him out to this man’s house, and he examined the cultivated land that had been worked on this principle. I took him out to meet this man and he stated that he had tried all of the methods known, over the width and breadth of the land. At that time, he seemed rather skeptical about this idea. He stated that he had put out some three hundred acres of potatoes and did not get the seed back. I asked him how he cultivated his land, and he described the methods used further east. Then I told him of this new method, and he went out to see this man. I said, “Now we are going out and see the only dry-farmer in the country,” and that was when I took him out to see Joe Barkhurst, this gentleman I have been telling you about, this gentleman from Otoe county – one of the very few men who had come out there with advanced ideas and who was able to adapt them to this country.

As soon as I introduced him to this man, I found that Mr. Campbell rapidly approved of his methods. He went over every foot of the place. In some places it was dry and in other places it was necessary to step over damp spots. Then we went over to the corn crib. He had the corn crib filled and he had bins of shelled corn, wheat, oats, and barley – all of which had been grown by this method, in addition to some four or five acres of small fruit. Mr. Campbell went over several parts of the field without any implements of any character, and with his hands dug down into the soil perhaps some six to nine inches, as far down as he could dig with his hands and brought up very desirable soil – soil deep enough and fit enough to grow any crop that could be grown there. He had several bottles into which he put some of this soil. Then he took samples of the different products that I have been telling you about and put them in different sacks.

Then we went across the farm and on over to dry land. As far as the eye could see, over thousands of acres, that same kind of dry land. He had an axe and he attempted to cut some of the soil or sod with that axe. It was as hard as this cement here. At a distance of forty rods away from this same cultivated land that I have been telling you about, he found soil that was that hard. He went around to see portions of the entire country that he found that same way. From the result of continuous droughts for three or four years, the soil had been so baked, and had attained such hardness, that by comparison with this land I was telling you about, it showed the success of this dry-farming venture.

Coming on down with him – not to tire you – for my time is limited, Mr. Campbell took those samples down to Omaha. He presented them to Mr. Holdrege there. Mr. Holdrege made him promise to go to down to Holdrege, Nebraska, where he had a farm, and he told Mr. Campbell that he could draw on him for any amount of money he wanted, but to go down there and make an experiment.

Mr. Campbell worked on some of those experiments all through the western Kansas country and even down to Oklahoma, where he found some very available land.

This land up in Box Butte County, at the time Mr. Barkhurst made his experiment, could be bought for $100 to $200 a quarter section. I sold one quarter section myself there for $185 because I did not think it was worth that much.

Under that system this man became the first dry-farmer. He is dead now, but he lived to see a thorough experiment of his plan and to see others adopt that method. Under that system of cultivation, you will find a successful and flourishing country. As a result of this, the entire Box Butte territory has come into prosperity, and Alliance is the center of this territory. The Box Butte table is farmed today largely by these identical methods first instituted by Mr. Joseph Barkhurst, the original dry-farmer in that country. Probably 75 or 80 per cent of that region I mentioned, of some thirty by thirty-six miles, is now under cultivation, and there is no county in the whole western part of Nebraska of the same size that has such fine soil and so much production as the Box Butte Table. I have not been speaking of the sand hills in general but have confined myself entirely to the Box Butte table, and not to the sand hill territory, which has its western limits in Sheridan county.

I am not going to take up your time to go into this matter any further, except that I want to say that the first original dry-farmer of the Box Butte table has proved to the country what Mr. Campbell had expounded, that this method could and has been successful.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -