William Whitmore and his brother raised hay commercially and bred and trained horses for sale. In 1880, he purchased the Valley Stockyard Company and served in the Nebraska Legislature in 1885 and 1887. In 1904, he was elected to the University of Nebraska Board of Regents where he promoted agricultural development.

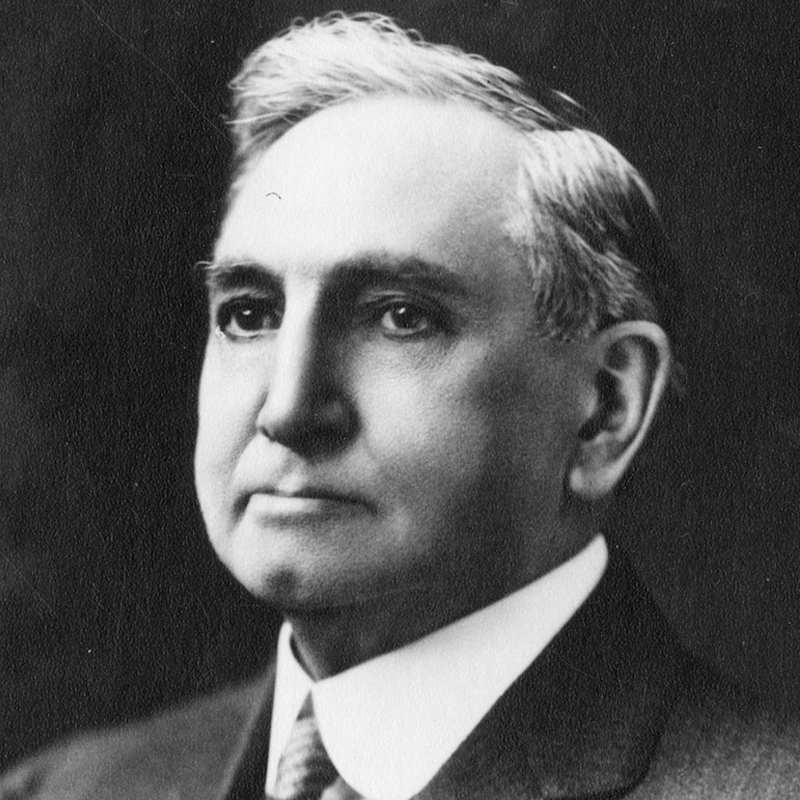

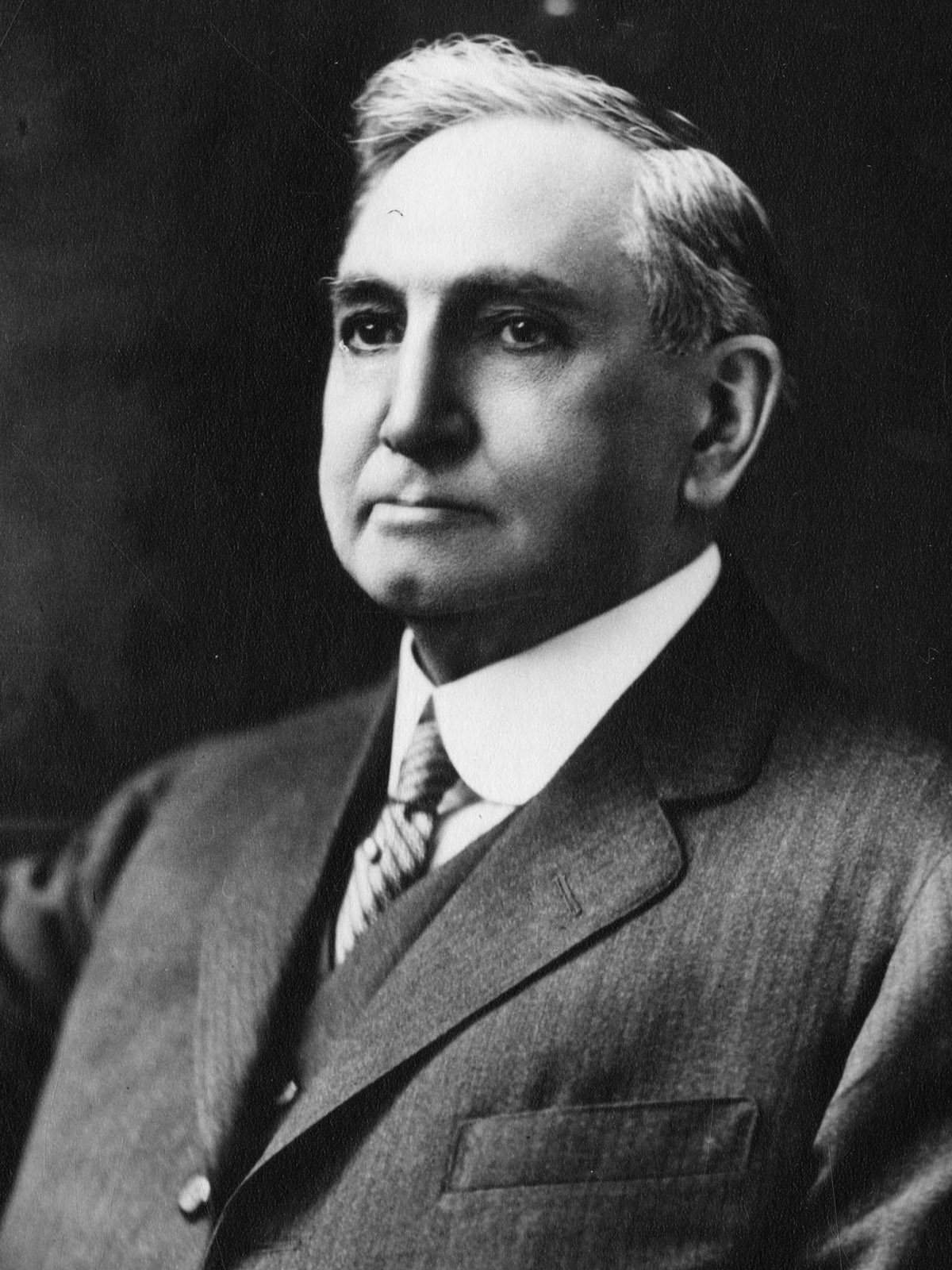

(Address delivered January 2, 1933, by S. Avery on the unveiling of a portrait of Mr. W.G. Whitmore, Nebraska Hall of Agricultural Achievement, College of Agriculture, University of Nebraska).

A Farmer Who Believed in Scientific Agriculture

The name Whitmore is of English origin. The oldest spelling seems to be Whytemere, which was modified into Whitmore, Whitemore, Whittemore, and Wetmore. Our ancestors were not careful in their spelling. One of the writer’s own ancestors spells his name in two different ways on the same page of a manuscript that has come down to us.

We have the record of a Whytemere serving in the wars of England about 1250, who appears to have been knighted for valor and, although definite proof is not at hand, all the Whitmore’s in America appear to have been descended from the same ancestral stock.

The man whom we honor today was a lineal descendant of one Francis Whitmore, born in England about 1625, admitted as a freeman of Cambridge, Massachusetts, presumably after a number of residences there, on May 3, 1654. The sone of this Francis, Francis (III), was born presumably at Cambridge on October 12, 1650. Francis (II) moved to Middletown, Connecticut, where his son, Francis (III), his grandson, Daniel (IV), and his great-grandson, Daniel (v), were born. The last-named Daniel (V) moved to Sunderland, Massachusetts, shortly before the American Revolution, in which he served with distinction as colonel. This Colonel Daniel Whitmore was a prominent figure in the affairs of the town of Sunderland. His son Jesse was the father of Charles who was the father of our William Gunn Whitmore. To use biblical language, “Now all the generations from Francis to William were eight.”

On his mother’s side, our Mr. Whitmore was descended from the equally distinguished Clapp family.

The subject of our sketch book was born June 23, 1849, at Sunderland. The writer has had the privilege of being a guest at the old Whitmore farm home. It overlooks the Connecticut River. One sees not far away the Sugarloaf Mountain and the Berkshire hills. Near the house is a beautiful waterfall where a little stream plunges down to meet the river. Philip Whitmore, a nephew of our Mr. Whitmore, with his family now lives on the old place and is an honored citizen of western Massachusetts. His children belong to the fifth generation of Whitmore’s to live on the ancestral farm.

Our Mr. Whitmore’s boyhood days were typical of the time and place in which he lived. We can picture parents toiling on the farm, the older boys serving in the Union army, the place operated through the efforts of the aging father, the women and girls, and perhaps a boy too young for military service. Mr. Whitmore was such a one and in the absence of three older brothers in the South, one of whom never returned, he assumed responsibility and acquired efficiency very early in life. After the war, with the return of two older brothers, he began what might be termed an independent career. With New England thrift he saved money and started a successful business at Turner’s Falls. In ’76 he was elected as representative to the Massachusetts legislature, and evidently looked forward to leading the life of a successful citizen of western Massachusetts. Fate, however, had a different career in store. The loss of wife and children while he was still young was perhaps the principal cause for his resolving to break away from the homeland and cast his lost with a new state, for on January 1, ’78, he wrote in his journal, “Lonely, lonely, lonely. These formerly happy anniversaries”, and on February 6, he noted, “I left via the Hoosac Tunnel for the West. God only knows where.”

A little later in his journal, we find him at Elgin, Illinois, looking up data in regard to the establishing of a cheese factory. The journal is silent in regard to his scrutiny of Nebraska farmlands. It is presumed that he traveled widely in eastern Nebraska in search of an ideal location. The biography by Mr. McIntosh in 1922 states this explicitly, the information probably came from Mr. Whitmore himself. At any rate, he and his brother Frank purchased a tract of land at Valley, which is not a part of the property of the Valley Stockyards Company, a successful corporation directed by his sons, Jesse and Burton.

When young men from New England came west, they naturally brought with them mental pictures of the homeland and sought for locations in Nebraska that did not represent too great changes from the old environment. Thus, when Isaac Pollard, whose portrait is seen in Hall of Agricultural Achievement, came from Vermont, the hills and rocks at Nehawka, as his son Ernest tells me, made a greater appeal to him than the level prairies. I have no doubt that the Whitmore brothers, coming from that long ribbon of fertility, the Connecticut valley, saw in the Platte valley a broader, longer, and more fertile strip of arable land, hay land, and pasture than even the best of New England could present - that, I take it, was one of the factors in deciding the location. They were valley dwellers in Massachusetts and became valley dwellers in Nebraska. Even the word Valley, the name of the town, must have had an unconscious appeal.

Mr. Whitmore’s journal is wonderfully illuminating in regard to his life in the latter part of the ‘70’s. He was a real dirt farmer in those days; such entries as “Planted corn”, “Hoed onion”, “Went to church and Sunday school”, “Thrashed”, “Bought six heifers”, “Debated in the Lyceum in favor of sound money”, - all of these show his daily round of life. They can be translated into the words, practical farming, industry, vision, and interest in social advancement. They show that while in his twenties he was active in public affairs. Most important of all are one or two very modest references to his being in company with Miss Knowlton, who as we know later became Mrs. Whitmore, his life companion and one of the most honored mothers in Nebraska.

Mr. Whitmore’s first public service in Nebraska of which I have any record was as a member, in 1884 and in 1886, of the Nebraska state legislature. He was elected by the voters of his home county but in his official acts, he represented the people of the entire state, not narrow or local interests. His support of the state university at that time was of critical importance and its results are felt even at the present time.

During Mr. Whitmore’s boyhood days, the minister of the Baptist church at North Sunderland, Massachusetts, was Parson Andrews. One of his sons, six years older than Mr. Whitmore, was E. Benjamen, who became a distinguished theologian, professor, and educator. Mr. Whitmore as a private citizen favored his coming to Nebraska as chancellor in the year ’90. Dr. Andrews’ contacts with agriculture had ceased in his boyhood, but he became on coming to Nebraska more enthusiastic for agriculture, agricultural education, and agricultural experimentation than any who had preceded him. The University of Nebraska school of agriculture had been started under Chancellor MacLean, but it was during Chancellor Andrews’ administration that the period of expansion began. Chancellor Andrews’ sympathies were always exceedingly broad and democratic. It was a fortunate thing for the university and for the state that on his coming here, he had Mr. Whitmore as a practical mentor and guide, who helped direct his broad interest in farming and his broad sympathy for farmers into practical channels. Though I never heard Mr. Whitmore say so specifically or found any record on the subject in his journal, I have no doubt that a desire to help Chancellor Andrews in every way, particularly in the development of scientific agriculture at the university, was an important factor in influencing him to accept the nomination for the office of regent and to take his place on the board in January, ’04. His colleagues at once made him chairman of the committee on industrial education. This was the committee of the board having agriculture in charge, and the entire development of the agricultural program of the university for many years received Mr. Whitmore’s approval and much of it came as the result of his initiative action.

The records of the board of regents for the following twelve years show that in spite of his large and growing business interests, his representing the state at national gatherings, and the constant attention given to a large and growing family, he almost never missed a regents’ meeting. It is reported that after he had been nominated in convention, he made one of the shortest speeches of acceptance on record. Orally the following has been transmitted: “If I am elected regent, I won’t be a dead one”. He was certainly very much alive from start to finish. I recall further that even after his term of office had expired, he went about the state on an automobile trip of inspection, as the guest and adviser of his old colleagues on the board and his successor in office.

Though I have mentioned especially his service to agriculture in connection with the development of the university, I would not convey the impression that agriculture in any sense caused him to lose sight of the interest of the university. During his services as regent, he was generally chairman of the committee of the board named to present all the needs of the university to the legislature. In this capacity he was exceedingly useful. He was no politician in the sense of offering quid pro quo. He secured votes through his sincerity, his fairness of presentation, and above all, through the confidence which he inspired. When malice and envy tried to involve the university in so-called investigations, it was common to hear among members the expression, “As long as men like Whitmore are on the board, I do not think we need to question the honest of the administration of the institution.” His presence on the board was accepted as a guarantee that the conduct of the regents was high-minded, and their official acts were inspired by a desire to promote the welfare of the state.

Another characteristic of Mr. Whitmore that displayed itself was his loyalty to his friends. He carefully avoided bestowing friendship on anyone unworthy of it and his friendship, once bestowed, was lasting. Beginning with Canfield, he was the friend and supporter of five successive chancellors. This is especially striking too as occurring in a state where loyalty to those in public office has never been a fetish. His loyalty, however, was not of the undiscriminating kind; it was that helpful, constructive loyalty which made everyone associating with him able to do his work in a better way because of the feeling that he had Mr. Whitmore’s support. This was especially true of those who were working for the advancement of agriculture through science.

One frequently reads in his journal items like this: “Attended the dedication of the law college building. Spoke in behalf of the regents.” In fact, he usually spoke in behalf of the regents at public gatherings. Few men have been able to perform such services more brilliantly. His wit was ready, his words well chosen, and his message always went straight home. Stories of his shafts of humor are still repeated. May I recall one? During his membership in the legislature, a fellow representative spoke in a very long and very dreary way. The house had about reached the limit of endurance when the “orator” paused to moisten his throat with a drink of water. Instantly Mr. Whitmore was on his feet with, “I rise to a point of order.” The speaker of the house recognized him and said, “The gentleman from Douglas will state his point of order.” “It is,” said Mr. Whitmore, “out of order for a windmill to try to run on water.” In the laughter that followed, the tiresome talker sat down.

I wish to relate a story that he once told to a group of friends in facetiously apologizing for his lack of small vices. On a trip with some cattlemen out through the range country, one of them said to him, “Whitmore, come back into the next pullman and have a drink.” “Thank you,” said Mr. Whitmore, “but I never learned to drink.” Pretty soon they were joined by another who said, “Whitmore, we need you at a little game of poker.” “I am sorry to disappoint you,” said Mr. Whitmore, “But I never learned the game.” A third one said, “Well, anyway, Whitmore, come along and look on and smoke a cigar.” “Thank you again,” said Mr. Whitmore, “but I have never used tobacco.” Finally, one of them said, “Whitmore, can you eat baled hay?” “No,” said Mr. Whitmore, “I can’t eat baled hay.” “I knew as much,” said the speaker, “You are no company for man or beast.” I wish I could have told this story as he used to tell it. I think he was willing everyone should know that he was a Puritan in conduct, but that he was not censorious of others. He lived according to the best code of the later Victorian age, but he showed a tolerance for others commendable in any age.

Those who have had the high privilege of enjoying the hospitality of the Whitmore home know what genial and gracious host and hostess Mr. and Mrs. Whitmore were. They built there a home from which good cheer radiated and which resulted not only in the development of the character of their own children but spread its influence throughout the entire community. His position in the community may be illustrated by the following story: I drove to Valley about twenty years ago in the first automobile I ever owned. To test it out Mr. Whitmore, Mr. Webb, his son-in-law, and I were putting the auto through its paces in the streets of the town. Mr. Webb was at the wheel. I can say in all sincerity that we were not going fast by modern standards, but not knowing whether Valley, like some other towns, might not have retained a six-mile speed limit, I suggested to Mr. Whitmore that there might be danger of some daily paper coming out with headlines, “President of the board of regents and chancellor of the university arrested in Valley for speeding.” Mr. Whitmore replied, “Well, since I am mayor, and Webb (who is doing the driving) is marshal, I believe you are safe.” After that, I put myself wholly in his charge when visiting his pleasant hometown.

Mr. Whitmore’s journal, under date of August 16, 1913, refers to this visit in Valley and speaks of our going to Omaha together to visit the medical college and the Child Saving Institute. The next entry of interest to me, made on June 5, 1914 was as follows: “Got all our tickets, and so forth, for our trip to Europe,” and the journal closes with this entry four days later, “Cutting grass and weeds in pasture. Closing up accounts to leave.” Mr. and Mrs. Whitmore were in Europe when the World War broke out. They made their way homeward through France with some difficulty. All the porters had gone to the war and in caring for his heavy baggage, his strength was over-taxed. Upon his return, he never seemed quite the same. The entries in his journal were not resumed; however, his public and private activities were not abated.

At the expiration of his second term as regent, he declined re-election and gradually retired from active participation in the business which he had largely created, leaving it in the hands of the sons whom he had trained. A little later he and Mrs. Whitmore moved to Lincoln and in this city, he passed the reminder of his life surrounded by his friends, children, and grandchildren. He was deeply honored by all those who knew him and accepted the tributes made to him by his friends graciously and not too seriously. Till the end came on October 13, 1931, he lived the kind of a life described by Shakespeare as: “That which should accompany old age, as honor, love, obedience, troops of friends.”

All in all, Mr. Whitmore was a great and successful citizen. I am not one who wishes to make a god of success, yet we must admit that success is one of the elements of greatness. One is especially great whose success in tangible and in intangible things promotes the advancement of others. Both he and the public benefited through the fortunate outcome of his endeavors. He contributed much to agriculture, especially through his ability to organize the forces devoted to agricultural advancement. Through his farming operations and his stockyards company, he added much to the wealth of the state and of the community. As a member of society, he set the finest possible example in all of the social virtues. He gave of his time and talent freely to cause of higher education. Someone has said that the average man is absolutely forgotten thirty years after his passing into the Great Beyond. Mr. Whitmore’s name, on the contrary, will always be known to those who interest themselves in the early development of Nebraska. To help perpetuate his memory and to do our small part in causing his achievements to be remembered is our main purpose in meeting here today to unveil his portrait to be placed in the Nebraska Hall of Agricultural Achievement.