Lawrence Bruner, state entomologist concerned with the grasshopper scourge in Nebraska, created an invention to deal with the insects and the devastation they caused - the “hopper dozer.” This trap could be made for less than $10.00 and could clear 40 acres in one day. A North Dakota grasshopper excursion netted 2,400 bushels of hoppers caught/killed and between 200,000 –300,000 bushels of wheat saved.

(Reprinted from The Nebraska Bird Review, v, pp. 35-48, April 30, 1937).

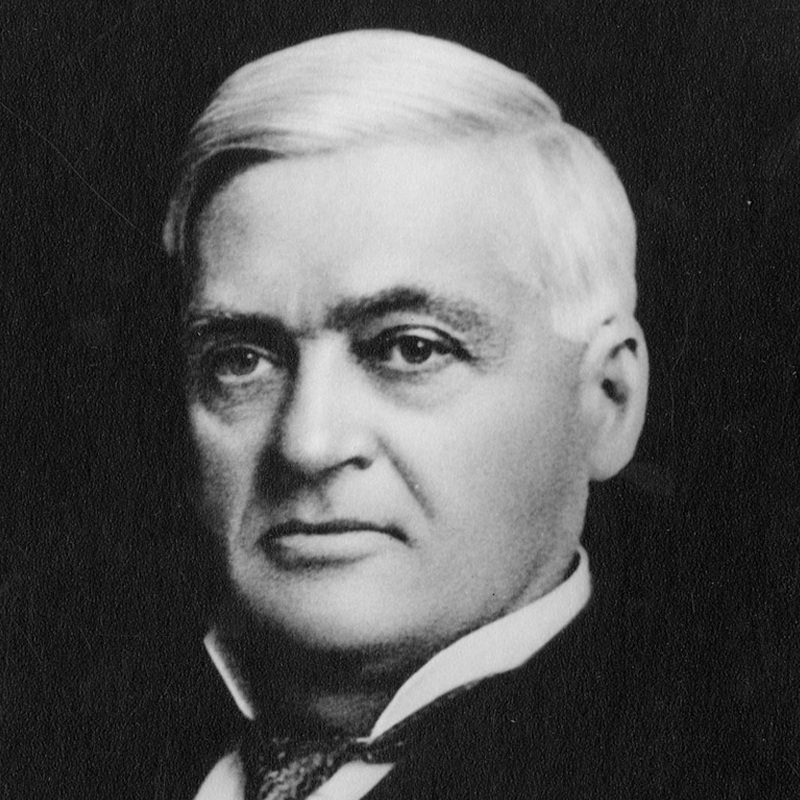

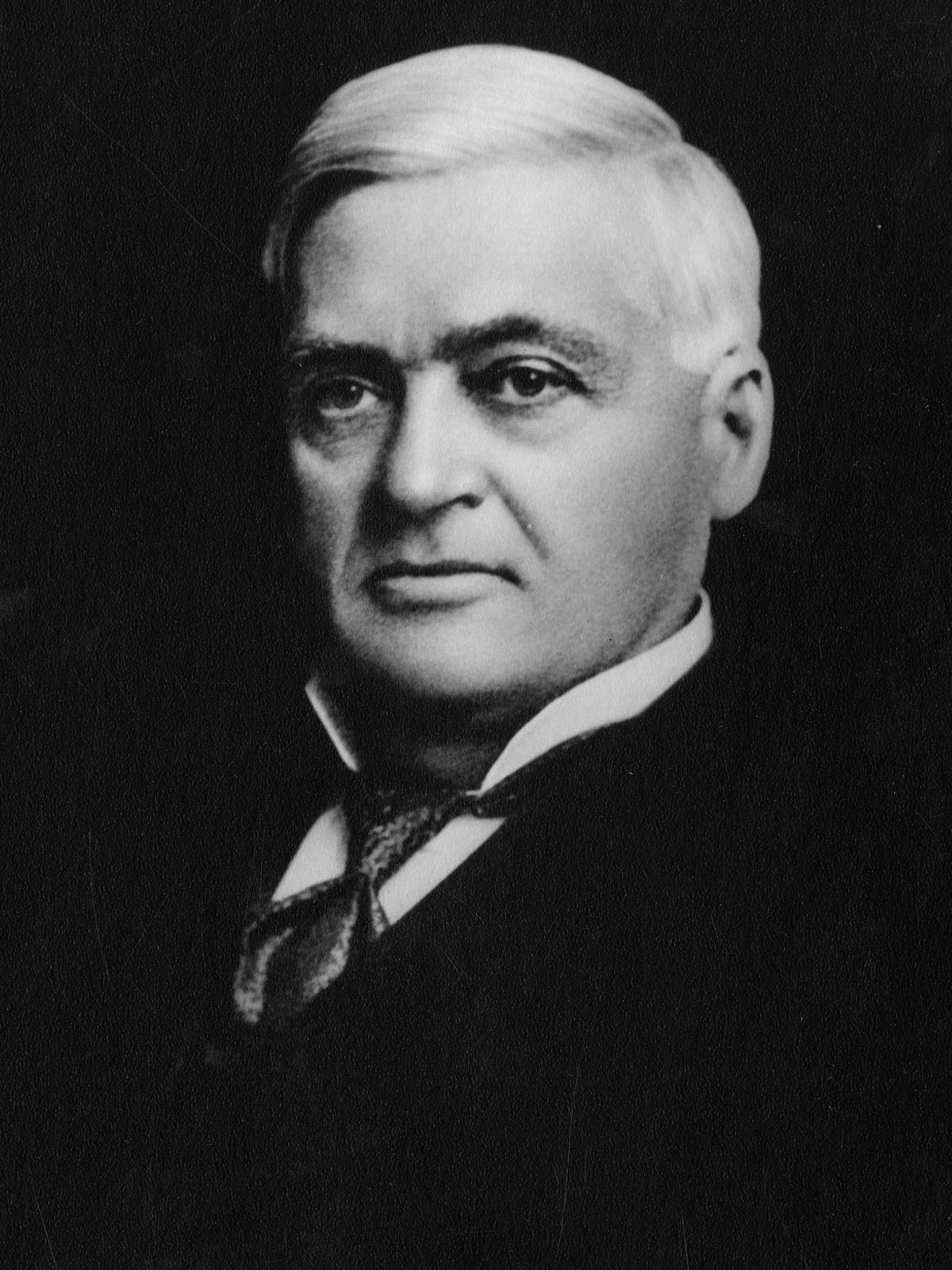

On January 30, 1937, at his home at 3033 Deakin Street in Berkeley, California, Lawrence Bruner, pioneer American economic entomologist and a world authority on grasshoppers and related insects (Orthoptera), as well as the person who more than any other individual was responsible for the organization of the Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union, passed away after a severe illness of a few days that culminated a rather extended period of gradually declining health. It is difficult to epitomize any account of the life accomplishments of this man, because they were so many and varied, and perhaps for this purpose there may very well be quoted some very recently written words of Herbert Osborn, another pioneer American entomologist who in age was just seventeen days Bruner’s junior, and who accompanied him on a collecting trip through Mexico in the late fall and winter if 1891, during which trip the two men collected insects as far south as the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Both men at the time were serving as Special Agents of the Division of Entomology of the United States Department of Agriculture, Bruner being located at the University of Nebraska and Osborn at Iowa State College. Subsequently Bruner remained connected with the Nebraska institution throughout his career, Osborn later become Professor of Zoology and Entomology at Ohio State University, one of America’s greatest teachers and research workers in entomology, and the recipient of many scientific honors. Professor Osborn (59) writes:

“The experiences of that (Mexican) trip cemented a life-long friendship. He (Bruner) was an unusual field naturalist, at home on the plains or in the mountains where he spent much time in studies of grasshoppers and other farm pasts. * * * Aside from his teaching and his training of a number of distinguished entomologists he will be known to future entomologists as author of a number of important papers on Orthoptera. Bruner * * * was one of the ‘field naturalists’ who was at home and most happy when in quest of birds, insects or other animals. His extensive field trips resulted in large accumulations of insects and, especially in Orthoptera, the Nebraska University collection is one of the richest in the country. The collection has been greatly extended by Swenk and Mickel and is no doubt very complete for Nebraska and the plains and prairie regions.”

Lawrence Bruner was born at Catasauqua, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, on March 2, 1856, the second child and eldest son of Uriah and Amelia (Brobst) Bruner, to who subsequently seven other children were born. In April of 1856, when the baby Lawrence was six weeks old, Uriah Bruner came to Nebraska with his wife and two children. The trip was made by railroad as far as Iowa City, Iowa, but since that was then the western terminus of the railroad, the journey to Omaha, Nebraska, was completed by stage coach. The family located on a farm near Omaha, and it was there that Lawrence spent his early boyhood. Even at this early period he was interested in natural history, and made many observations on birds, mammals and insects, these frequently being of considerable importance, as for example his recollections concerning what he saw of the Eskimo Curlew when he was a boy ten to twelve years of age, from 1866 to 1868, as published in 1915 (60) by the writer of this obituary.

About the time that the town of West Point, Nebraska, was founded, the Bruners removed from the farm near Omaha on which they had been living to the new Cuming County settlement, and constituted on of the pioneer families of that place. From 1869 until he entered the service of the University of Nebraska in 1888, West Point was the home town of Lawrence Bruner, and many of his most valuable early observations in the field of natural science were made in the vicinity of that place. In addition to the education that he received in his own home, re received instructions at Jones’ Select Academy in Omaha and under the tutelage of Professor Samuel Aughey and others at the University of Nebraska, which latter institution had been chartered at about the time the Bruner family had removed to West Point, and on the Board of Regents of which Uriah Bruner served during this early period. The old Bruner home at West Point is still occupied by members of the family.

But the great interest of Lawrence Bruner was in the fields and woods, rather than in formal instruction in the school room. He learned the art of taxidermy, and started mounting birds and mammals, first for himself and later for others as a means of securing personal funds for the furtherance of his natural history studies. His commercial taxidermy record book, now in the custody of the writer, and covering the period from the fall of 1880 to the fall of 1887, shows that during these years he mounted over one thousand specimens of birds and mammals for himself and others, especially during the winter months when he was not engaged in the entomological service of the Federal government. He began to develop some local popular fame, probably not so much for the value of his insect studies, which was a real and great one, but because many of the good citizens of West Point and elsewhere in pioneer Nebraska could not then understand how any practical good could come of hours spent studying grasshoppers, ants and other “bugs”, and, not always silently, as Bruner himself often jocularly related in later years, conjectured as to the real mental status of this devotee of the insects.

The years 1873 to 1876 are remembered in Nebraska as the “grasshopper years”, because of the general invasions of this area by the Rocky Mountain grasshopper, which reached its height in the disastrous invasion of 1874. Loss of crops and business because of these continued depredations ran into the hundreds of millions of dollars in this recently settled agricultural region, and for a time it seemed might provide a permanent blight upon the development of the state. Lawrence Bruner witnesses these invasions and their terrific toll, and was greatly impressed thereby. He began to make an even more serious study of grasshoppers, collecting and distinguishing the different species, and studying their habits, as well as learning all he could about their life histories and means of controlling them. Thus began an interest that was to make him a world authority on the grasshoppers and related insects.

Bruner’s first technical contribution in entomology was a paper published in 1876 (2), entitled “New Species of Nebraska Acrididae”. The fact that two of the three supposed new species there described proved to be synonyms indicates the difficulties in the matter of inadequate literature that the isolated worker in Nebraska was experiencing. The following year, Bruner (3) published a list of the grasshoppers that he had found in Nebraska, totaling ninety-five species for the state. Following the appearance of this list, Bruner discontinued publication along systematic lines for seven years, by which time he had established connections with the National Museum at Washington and with his senior American authority on the Orthoptera, Samuel H. Scudder (1837-1911) of Harvard University, who for a number of years introduced to science Bruner’s numerous insect novelties as they were forwarded to him.

By an act of Congress approved March 3, 1877, the three most learned economic entomologists in the United States - Charles V. Riley (1843-1895), the great organizer of economic entomology in this country, then serving as the State Entomologist of Missouri; Alpheus S. Packard, Jr. (1839-1905), one of the greatest American entomologists and at the time director of the Peabody Academy of Science and chief editor of the American Naturalist; and Cyrus Thomas (1825-1910), one of the foremost early economic entomologists of America, and then serving as State Entomologist of Illinois - were appointed to form the United States Entomological Commission and to investigate and report upon the depredations of the Rocky Mountain grasshopper in the West, and especially as to the best practicable method of preventing these annual invasions. Riley visited Nebraska in June of 1877, and Thomas also visited the state that year. They needed trained help in their investigations, and what was more natural than that they should learn about and contact this Nebraska you man, now just attaining his majority, who had shown such an interest in grasshoppers and all other forms of animate life. Lawrence Bruner began to assist the Commission in these grasshopper investigations in 1878, at first on a temporary basis, but in 1880 he was formally appointed as an assistant to the Commission. He served the Commission, and later the Division of Entomology of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, for the ensuing eight years.

Bruner’s first assignment with the Commission, under the direction of Dr. Packard, was to investigate the status of the Rocky Mountain grasshopper in Montana. On July 4, 1880, he left Omaha by rail for St. Paul, and thence to Bismarck, (North) Dakota, and on to Green River, about 100 miles to the west, and thence by stage to Miles City, Fort Keogh, Terrey’s Landing at the mouth of the Big Horn River, and up the Yellowstone River to near Bozeman, thence down the Gallatin to its junction with the Madison and Jefferson Rivers on over the country to Helena and Fort Shaw, and down the Missouri River to Fort Benton, and from there by stage back to Fort Shaw and Helena, thus covering much of western (North) Dakota and central Montana. The following summer, 1881, under the direction of Professor Riley, Bruner worked first in the vicinity of Greeley, Colorado, and thence westward along the line of the Union Pacific Railroad into Wyoming, Utah and Idaho, especially in the Green, Bear, Snake, Big Hole, Deer Lodge, Hellgate, and Missoula River valleys. From Missoula he proceeded on horseback across the Coeur d’Alene Mountains and through northern Idaho into Washington Territory, thence to Walla Walla and down the Columbia River to Portland and Astoria, and by steamer to San Francisco. The results of these two years’ investigations by Bruner were published in full in 1883 (4). Several weeks after his return from this last-mentioned field trip, Bruner married Miss Marcia Dewell of Little Sioux, Iowa, on Christmas Day of 1881, going to Washington D.C., on his wedding trip. Later they took up their residence at West Point, Nebraska, with time spent in some winters at Washington.

In the summer of 1882, again under Riley’s direction, Bruner left West Point by rail on June 20 for Bismarck, (North) Dakota, thence by river to Fort Benton, Montana, and finally by state on to Fort McLeod, British America, going into camp forty-five miles west of that place, where for a month he studied the Rocky Mountain grasshopper on its breeding grounds. Then a boat was built and the return made down the Saskatchewan River to Medicine Hat, thence by team to Fort Walsh, and then a ten days’ drive to the terminus of the Canadian Pacific Railway, which was taken to Winnipeg, from which return was made to Nebraska. Many important observations were made on this trip, also, which Bruner (5) reported in detail upon his return, and which were also published in 1883.

It became desirable, in the summer of 1883, again to make a study in the Rocky Mountain region as to the prospects for 1884 in connection with the Rocky Mountain grasshopper, and again Dr. Riley selected Bruner to do the job. With an assistant he left West Point by rail for Albuquerque, New Mexico, from which place they proceeded northward to the Taos Valley, where they were much inconvenienced by the prevalence of smallpox in the various valleys, but eventually succeeded in getting the desired information. They then proceeded by wagon along a route where it was often difficult to obtain the necessities of life, to Fort Garland, Colorado, where the weather turned cold with a snow storm, and Bruner’s assistant became ill. As soon as possible, the journey was resumed by rail to Denver, and thence to Fort Collins, from which they proceeded by wagon to the North Park in Colorado, and on to Laramie, Wyoming. From Laramie they took the Union Pacific Railroad to Rock Creek, then the stage to Junction City, Montana, then along the eastern flanks of the Big Horn Mountains between Forts Fetterman and McKinney. Returning to Junction City, they went to Bozeman, and on horseback proceeded by way of the valleys of the Yellowstone, Upper Madison and Snake Rivers into the valley of the Salmon River to Salmon City, Idaho. The summer being well spent, they then went by rail to Ogden, Utah, and from there they returned to West Point, and Washington, D.C. Bruner’s (6) report on this summer’s work was published in 1884. When, on February 29, 1884, the Entomological Society of Washington was organized at Dr. Riley’s home in Washington, Lawrence Bruner became one of the charter members of that organization.

Bruner spent the summer of 1884 largely in Nebraska. In that year, Dr. Riley had him appointed to serve as Special Agent for the Division of Entomology to engage further in the study of grasshoppers, not so much on their breeding grounds in the Northwest, but on their area of occupancy known as the “Temporary Region”, in which the state of Nebraska was included. Bruner’s headquarters were at West Point, but he travelled considerably within Nebraska and studied not only the Rocky Mountain and other grasshoppers, but also the chinch bug, cutworms, Colorado potato beetle, cabbage worm, snowy tree-cricket, and various pests of native willows and cottonwoods (10). But the following summer Rocky Mountain grasshopper investigations in the Northwest again became necessary, and, under Dr. Riley’s direction, in July and early August Bruner went to Glendive, Montana, from which point he worked down the Yellowstone River Valley to its junction with the Missouri River at Fort Buford, thence along the Missouri to Bismarck, (North) Dakota, and across country Harold, on the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad, and back to West Point (12). The greater part of the year 1886 Bruner spent studying insect pests in Nebraska, especially grasshoppers and on April 17, under instructions from Dr. Riley, he visited the Brazos River region in Washington County, Texas, and surround areas, to investigate a severe grasshopper outbreak in that region, returning to West Point on May 14 (13). His field of labor in 1887 was in the state of Nebraska and adjoining regions, with West Point as headquarters, where observations were made on a rather large number of common pests of the region (14).

After the establishment of the University of Nebraska in 1869, and during the subsequent period of Rocky Mountain grasshopper invasions of Nebraska, especially from 1871 to 1878, Professor Samuel Aughey, then Professor of Natural Sciences in the University, gave considerable attention to the usefulness of birds as grasshopper destroyers. In 1877 he submitted to Cyrus Thomas of the U.S. Entomological Commission an extensive and pioneering report on this subject entitled Notes on the Nature of the Food of the Birds of Nebraska, in which the role of birds as insect-destroyers was discussed in great detail, with proof based on personal examination of stomachs of birds, which report was published in 1878 (1). Without doubt Bruner’s contact with Professor Aughey during the 1870’s had much to do with his subsequent life-long interest in the economic value of birds as destroyers of grasshoppers and other insect pests.

Professor Aughey was interested no only in grasshoppers, but also gave attention to investigations of the chinch bug, Hessian fly, and others of the more troublesome insect pests found in Nebraska. When the Nebraska Agricultural Experiment Station was organized, in 1887, Mr. Conway McMillan was appointed as Entomologist, and he prepared a report on “Twenty-two Common Insects of Nebraska” (58), which was the second bulletin published by the newly established Nebraska Station. When Mr. McMillan resigned this position, in March, 1888, to accept a professorship of botany in the University of Minnesota, it was wholly logical that the place should be offered to Bruner. He accepts it, removed from West Point to Lincoln, and in April, 1888, became Entomologist of the Nebraska Station. Also he continued to make annual reports to the Division of Entomology as its Special Field Agent, covering local or special assignments, during the following six year. Such reports were made for 1888 (15); 1889 (16); 1890 (18), this being a report on the insects of sugar beets, which industry was just starting near Grand Island; 1891 (20), this being a report on field work done during the summer in portions of Colorado, Wyoming, the Dakotas, Minnesota, Montana, Idaho, Utah, and along the Red River Valley of Manitoba; 1892 (23); and 1893 (25), this being a report on personal investigations of insect outbreaks in Nebraska and of grasshoppers near Grand Junction, Colorado, and in western Nebraska and eastern Wyoming. In 1894, the several Special Agents of the Division of Entomology were discontinued by order of J. Sterling Morton, then Secretary of Agriculture, thus terminating Bruner’s official connection with the Division. Nevertheless, he submitted reports for 1895 and 1896 as a Temporary Field Agent of the Division (29), these being reports on grasshopper conditions in Colorado, Wyoming and Nebraska for the two years mentioned.

Beginning with the 1888 report and continuing through the 1903 report, except for the years 1889 and 1894, Bruner prepared a series of contributions for the Annual Report of the Nebraska State Board of Agriculture, under the title of “Report of the Entomologist”, first as Entomologist at the State University and later as Entomologist for the State Board. The reports for 1900 and 1903, published respectively in 1901 and 1904, dealt with ornithology, and were substantially identical with the second volume of the Proceedings of the Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union and the Preliminary Review of the Birds of Nebraska. Similarly, beginning with the 1889 report of the Nebraska State Horticultural Society and continuing through the 1906 report, except for the years 1892, 1898 and 1905, reports were prepared by Professor Bruner, or under his direction, those for 1896, 1903 and 1904 dealing with birds, the others with insect pests.

In 1893, Bruner (22) published his first general economic account on the destructive grasshoppers of North America. It was also in 1893 that he began the publication of popular articles in the Nebraska Farmer, dealing with a great variety of the common insect pests of Nebraska, in effort more widely to disseminate information on insect pests and their control among the farmers of the state, supplementing his more formal reports issued from time to time through the bulletins of the Nebraska Agricultural Experiment Station. These popular articles were continued from time to time until 1904. In these articles he frequently referred to the economic value of our birds as insect destroyers, notably in one on “The Utility of Birds” in the Nebraska Farmer for July 24, 1902. It should also be mentioned that early in 1899 he had prepared a four-page leaflet entitled “A Plea for the Protection of Our Birds” (32), which was given an exceedingly wide circulation in Nebraska and had a marked effect in promoting popular interest in this subject among our citizens. It was later reprinted by the N.O.U. to effect an even wider distribution in the state.

In 1894, Bruner (26) combined his 1893 report to the State Board of Agriculture, entitled “A Preliminary Introduction to the Study of Entomology” with his report on “Insect Enemies of the Apple Tree and Its Fruit” from the State Horticultural Society report for 1894 and on “The Insect Enemies of Small Grains” from the State Board report for 1892, into a single volume under the first-mentioned title, which was much used in the schools and by farmers requiring an elementary knowledge of entomology. His only other interest in a text-book was when he wrote the chapters on animal life (v-viii) for the New Elementary Agriculture (36), which was prepared in collaboration with Professors C.E. Bessey and G.D. Swezey, respectively, his colleagues in the Department of Botany and Astronomy on the University of Nebraska faculty, and published in 1903.

The Nebraska legislature of 1893 officially enlarge the duties of certain professors of the University of Nebraska, and under this act the instructor in entomology in the University was made the acting State Entomologist, with the duty of answering inquiries concerning insect pests, and subsequently of inspecting for the presence of dangerous insect pests, all of the nurseries in the state where such inspections were desired, and to certify as to the findings. From 1898 on, under the provisions of this act, Bruner commonly used the title of State Entomologist. The legislatures of 1901, 1905, 1097 and 1909 made special appropriations directly to him as State Entomologist for the carrying on of insect control work in the state, especially with chinch bugs and grasshoppers. A law passed by the legislature in 1911 merged this independent activity of the State Entomologist with his regular duties in the University and Experiment Station, without abandoning the title.

Prior to Bruner’s appointment as Entomologist at the Nebraska Agricultural Experiment Station, no formal instruction in entomology had been given or offered to the students at the University of Nebraska. But in the fall of 1888, a few months after his becoming established in Lincoln, several students in the Botanical Seminar of the University who were greatly interested in natural history asked him to offer a course that would aid them in securing some knowledge of insect life. This was done, and the informal arrangement was continued until in 1890, when entomology was offered regularly as a course in the old Industrial College under Bruner as instructor in Entomology, which more formal arrangement continued until 1895, when the Regents of the University set up the Department of Entomology and Ornithology under Bruner as the Professor.

During these early years, as well as subsequently, Professor Bruner was assisted by various students specializing in entomology or ornithology, or both, who were engaged by either the University of the Experiment Station. These he always referred to as his “boys”. The first of them was Herbert Marsland, who assumed duty as an assistant shortly after Professor Bruner removed to Lincoln, and continued to prove useful during 1889 and 1890. During 1890 and early 1891, Thomas A. Williams (deceased 1900) was also associated with Professor Bruner, working on his classic study of Nebraska aphids or plant lice. In 1893, Harry G. Barber, now a leading authority on Hemiptera and custodian of the collections in this order at the United States National Museum, became associated with Professor Bruner as Assistant Entomologist in the Experiment Station, and continued so to serve during 1894 and 1895, doing much valuable economic work during these chinch-bug-ridden years, but resigning on July 1, 1895, to carry on elsewhere as a biology teacher and entomologist. His place was immediately taken by the late Walter D. Hunter (deceased 1925), who acted as Instructor in Entomology and Assistant Entomologist in the Experiment Station until his resignation in 1900 to accept a similar position at Iowa State College. Mr. Hunter joined the Bureau of Entomology of the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1901, and the following year was placed in charge of the cotton boll weevil investigations, and in 1909 of all southern field crop pests and the tick investigations of the Bureau.

Having become responsible in 1895 for the work of the University in the field of ornithology as well as entomology, Professor Bruner felt a growing interest in the preparation of a revised list of the birds of the state. There had been no state list published since the appearance in 1878 of Samuel Aughey’s (1) pioneer notes on Nebraska birds, except the “Catalogue of Nebraska Birds” compiled by Professor W. Edgar Taylor, then of the State Normal at Peru, Nebraska, and the unfinished “Notes on Nebraska Birds” published jointly by him and A.H. Van Vleet in 1888 and 1889. Professor Bruner had been taking an active interest in Nebraska birds since the early 1870’s, and many interesting specimens had passed through his hands while he was doing much private and commercial taxidermy work in the state. In short, he then knew more about Nebraska birds than any other living man. He had been elected in 1891 as a standing committee of one to cover the fields of both entomology and ornithology for the Nebraska State Horticultural Society, and when in 1894 the then Secretary of the Society, Professor Frederick W. Taylor, suggested that he prepare a report on the birds of Nebraska for a portion of an early succeeding annual report, in place of his usual report as Entomologist, the proposal was accepted immediately.

Professor Bruner took up this new task at once with much enthusiasm. He wrote to all persons known to him to be interested in Nebraska birds, requesting transcripts of their lists and notes, with the result that about forty individuals contributed data for the forthcoming report. Finding that information was especially incomplete concerning the wintering birds of the Pine Ridge region in extreme northwestern Nebraska, Professor Bruner studied and collected birds in Sioux and Dawes Counties in mid-December of 1895; and, finding much of interest, returned there in mid-February of 1896, with his assistant, Walter D. Hunter, and Lawrence Skow, the well-known Omaha taxidermist and bird lover, to help him out in further collections and studies. With all this material brought together, reviewed, edited and arranged, during the early part of 1896, Professor Bruner prepared the manuscript of his report entitled “Some Notes on Nebraska Birds” (28), closing the record as of April 22, 1896. In this report 415 species and subspecies were listed for the state, of which 227 were recorded as breeders. Reprints of this report, in both paper and cloth covers, were widely distributed by him, and it forms the real basis of our modern study of Nebraska ornithology.

Continued ravages by grasshoppers in the Argentine had by the close of 1896 become so serious that in January of 1897 a group of business firms at Buenos Aires organized what was known as the Merchants’ Locust Investigations Commission of Buenos Aires, to underwrite a scientific investigation of the situation. Through the Minister of the United States to the Argentine Republic, the Honorable W.J. Buchanan, the services of Professor Bruner Were secured to make this investigation and report. Accordingly, under a leave’s year of absence from the University, Professor Bruner sailed for Buenos Aires in the spring of 1897, arriving there on June 1. He Made the required investigations and early in February of 1898 submitted his report, starting back for the United States on February 27, bringing with him a large collection of Argentine insects and birds. During his absence in Argentina, the Department of Entomology was in charge of Walter D. Hunter. Bruner’s first report was published by the Commission in March, 1898 (31), and a second, more technical, report was published in 1900 (33), Three years after his return to the University. In recognition of his achievements, at the Commencement following his return, on June 8, 1897, the University of Nebraska conferred the honorary degree of Bachelor of Science upon Professor Bruner. His next honor was to be elected as President of the American Association of Economic Entomologists at its eleventh annual meeting at Columbus, Ohio, on August 18, 1899.

It was in 1899 that Professor Bruner, Dr. Wolcott and others set about organizing the Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union. This organization was developed first, during the late winter of 1898-99, as the Nebraska Ornithological Club, with its membership largely concentrated at Lincoln. In May of 1899 it merged with the Nebraska Ornithologists’ Association, that had just been organized under the sponsorship of I.S. Trostler of Omaha and others, and forty-three persons participated in the election of officers that was carried out by Mail ballot these succeeding July 15. Professor Bruner was elected as the first President of the new organization, which was called the Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union, and again served as its President in the year 1913014. The new officers called the 1st annual meeting at Lincoln on December 26, 1899. The details of the start of this organization have been given elsewhere by Mr. Trostler (61) and the writer (antea, ii, pp. 24-25).

The preceding reference to Professor Bruner’s 1896 report on Nebraska birds incites some poignant memories. At the time of the publication of that report, and for a few years previously, the writer had been interested as a boy Anne watching the birds in the vicinity of Beatrice, Gage County, trying to learn their names as best he could with the scanty literature available to him. He first began to take this bird study seriously when, on September 4, 1897, he identified a pair of Swallow-tailed Kites flying over his home, which observation is the initial one in his bird journals. In these years he did not know of Professor Bruner, or of his report, and it was not until in January of 1898 that he learned of the report and examined a copy of it at the Beatrice City Library. from this time on the ornithological enthusiasm of the writer waxed greatly, and before the close of 1898 he had started an oological collection and began to Mount birds, following instructions found in Apgar’s Birds of the United States. But He still desired a copy of Professor Bruner’s report, and, most of all, to meet the man himself So, in the spring of 1899, he mustered courage to write Professor Bruner about some birds that he had seen, receiving a prompt and most kindly reply, as well as an invitation to call and to become a charter member of the Nebraska Ornithologists’ Union, which, as just stated, was then under process of organization. The actual meeting, which occurred the following September in Professor Bruner’s office has always been a red-letter day to the writer. The forty-three year old man, much superior knowledge and experience about birds, and on a busy day, gave up a large part of his afternoon telling the 16 year old lad about his recent trip to South America, showing him the specimens of bird skins and eggs brought back, as well as the insects collected, giving him a copy of the 1896 report and encouraging him to enter the University upon graduation from the Beatrice High School. That is what actually subsequently took place in the fall of 1901, and on April 14, 1902, the writer became one of Professor Bruner’s assistants in the Department, thus starting a fine friendship that was to endure for the ensuing thirty-five years.

after his first technical contributions to North American orthopterology, in 1876 and 1877 (2,3), Bruner did not resume publication along these lines until 1884 (7), following which, for two decades, he published rather frequently on this subject. In 1885 (9) and 1886 (1), he published two contributions on Kansas Orthoptera, as well as some more general papers in the Canadian Entomologist (8); and later he published papers in that same periodical (19), the Proceedings of the United Station National Museum (17), Entomological News (21), and numerous others. His first catalogue of Nebraska Orthoptera appeared in 1893 (24), and this was revised more or less in 1897 (30) and 1903 (35). About 1895, his chief interest began to turn to exotic Orthoptera and this was followed by numerous publications dealing with this order of insects as represented in Nicaragua (27), Paraguay (47, 49, 51), South America in general (46, 48, 50, 52, 53, 56), Madagascar and East Africa (44), the Fiji Islands (55) and West Africa (57).

In the late 1870’s there had been started in London the publication of a monumental work, in parts, on “the flora and fauna of Mexico and Central America” under the editorship of Messrs. T. Ducane Godman and Osbert Salvin, known as the Biologia Centrali-Americana. Among those parts dealing with the insects, the beetles and the butterflies were started as early as 1879, followed by the true bugs in 1880, and Homoptera and moths in 1881, the Hymenoptera in 1883, the true flies in 1886, the Neuroptera in 1892, and the Orthoptera in 1893. In the latter order the earwigs, cockroaches and mantids were started in 1893, the crickets in 1896, and the long- horned grasshoppers in 1897, and these families were all finished by 1899 by European orthopterists, chiefly Dr. Henri de Saussure of Geneva, Switzerland. But That left the enormous group of true locusts, or grasshoppers, still to be done, equaling in volume all of the other orthopterous families combined, an because of failing eyesight, Dr. de Saussure was unable to continue this vast task. Professor Bruner was the world authority to whom Messrs. Godman and Silvin turned in this dilemma, and in 1899 he agreed to complete the work. From the first appearance of the first part of the second volume of the Biologia Orthoptera, in June, 1900, to the conclusion of the treatment of the grasshoppers in November, 1908, constituting 340 of the 376 pages of the second volume (which included also the walkingsticks as done by C. Brunner von Wattenwyl of Vienna, Austria), Professor Bruner devoted practically every minute of his time that was not demanded by his numerous regular University duties to the preparation of this, his greatest single contribution to systematic entomology.

In 1898, when taxidermy was added as part of the instructional work of the Department of Entomology, Walter D. Hunter’s younger brother, Joseph S. Hunter, was employed as an instructor in that subject, and continued in that capacity until this work was abandoned in 1901, when he removed to California, to take up work in economic ornithology and later in the game warden service of that state. Immediately after Walter D. Hunter resigned in 1900, J.C. Crawford, Jr., coming from Professor Bruner’s home town of West Point, took over the vacated entomology assistantship; and at the same time M.A. Carriker, Jr., of Nebraska City, took over the assistantship in ornithology, and Merritt Cary, of Neligh, entered the Department to start a serious study on the mammals of the state, as well as assist in investigations on the birds and butterflies. Messrs. Carriker and Cary made extensive collections of insects, birds and mammals in the Pine Ridge region of Nebraska in the early summer of 1901, following which Professor Bruner and Mr. Carriker investigated an increasingly serious grasshopper situation in western Nebraska, eastern Colorado and eastern and central Wyoming (34). Late In the winter of 1901-02 Professor Bruner, accompanied by Messrs. Carriker and Cary, went to Costa Rica on a short collecting expedition, during which a great deal of valuable Natural History material was secured and brought back.

Upon his return from Costa Rica, and after the close of the summer school in 1902, Professor Bruner organized an expedition under J.C. Crawford, Jr., to make a biological survey of the lower Niobrara River region. W. Dwight Pierce of Omaha and the writer accompanied Mr. Crawford on the trip. Most of the month of June was spent around a camp located near the old bridge crossing the Niobrara between Bassett and Springview, and thence down to Carns, Keya Paha County, where in July Professor Bruner joined the party, which then slowly preceded during the next month by flatboat and canoe to the mouth of the Niobrara. Enormous collections of insects, and many vertebrates as well, were taken on this expedition. In 1903, Messrs. Crawford and Carriker decided to return to Costa Rica where they did considerable additional collecting of insects, birds and mammals in that country. On their return in 1904, Mr. Crawford enter the employ of the Bureau of Entomology and later was appointed Assistant Curator of the Division of Insects in the United States National Museum, which position he held for a number of years, becoming an authority on the Hymenoptera. Mr. Carriker, whose insect specialty was the biting lice (Mallophaga), remained in Costa Rica until 1908, making extensive collections of vertebrate animals and insects there. The birds are now in the Carnegie Museum at Pittsburgh and the mammals in the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Returning to South America in 1909, Carriker continued his collections from the Island of Trinidad into Venezuela, to the headwaters of the Orinoco and across to the Pacific Ocean, and has since spent much time in South America collecting for the Carnegie Museum and the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences. Mr. Cary, from 1902 until the time of his death, was in the employ of the Biological Survey of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

When Mr. Crawford started for Costa Rica in 1903, W. Dwight Pierce, who had entered the Department as a majoring student in 1901, became Professor Bruner’s assistant. Upon His graduation in 1904, Mr. Pierce departed for Mississippi to become Assistant State Entomologist there, and later saw some years of service with the Bureau of Entomology on cotton boll weevil investigations under Walter d. Hunter. Meantime, in 1904, the writer replaced Pierce as Professor Bruner’s first assistant; and also assisting in the Department, beginning in 1904, were Harry Scott Smith (now Professor of Entomology at the University of California, located at Riverside) and Paul R. Jones (now in the insecticide business and residing at Beverly Hills, California). It may seem odd to some readers of this sketch of Professor Bruner’s life and work that the writer should make so much mention of the several “boys’ who assisted him from time to time in his labors, but any one of them can testify, as now does the writer, how their interests and work were intertwined and guided by those of Professor Bruner himself, so that in a large sense their activities during these years became also his interests. During these years, and especially from 1900 to 1910, Professor Bruner’s home at 2314 South 17th Street in Lincoln became largely the leisure-time rendezvous of all of these “boys”, and not only his “den”, in which his collections and library were kept, was open to them, but his entire home radiated the openhanded hospitality of Professor and Mrs. Bruner and family.

As Far back as 1885 poisoned bran baits had been used on a limited scale to destroy grasshoppers, but because these were scattered over the ground in lumps or piles they were found sometimes to poison poultry or useful native birds. Professor Bruner had checked the results of the use of poison brand baits in western Nebraska in the summer of 1901 (35), But he had not tested another poisoned bait for grasshoppers known as the “Criddle mixture” that was supposed to be relatively unattractive to birds and domestic animals. He decided to test the “Criddle mixture” in the summer of 1903, and the writer assisted him in these investigations, which were made in southwestern Nebraska, and were followed by an insect-collecting trip into Colorado. In January of 1904, Professor Bruner completed arrangements with Hon. Robert W. Furnas, the Secretary of the Nebraska State Board of Agriculture, for the publication of the Preliminary Review of the Birds of Nebraska (37), of which he was the senior author, in the 1903 annual report of the Board, and he spring much of the following spring and summer in helping prepare the manuscript, compile the index and read the proof of this work, which was published in separate form early the following September.

During the summer of 1905, and also that of 1906 after a trip into the Thomas County sandhills, where during May he assisted Frank M. Chapman and party to gather the material for the Greater Prairie Chicken group in the American Museum of Natural History, Professor Bruner led collecting parties in the Pine Ridge of Sioux County, Nebraska, with head camped located near Glen, on the White River, accompanied by Messrs. Jones, Smith and the writer. During these summers thousands of specimens of pinned insects were secured, as well as a good series of the small mammals of that region. Mr. Jones entered the service of the Bureau of Entomology in 1907, and Mr. Smith, after taking his Master’s degree in 1908, also entered the Bureau service. Mr. Jones’ position was filled for the year by W.H. Goodwin and when he engaged in the fall of 1908 as Assistant Entomologist in the Ohio Agricultural Experiment Station, his place was taken by Charles H. Gable, who in turn entered the service of the Bureau of Entomology in 1910, and was succeeded in 1911 by John T. Zimmer, now Curator of Birds at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, left Nebraska to take up entomological work in British Papua in 1911, later turning to ornithology and collecting in the Philippine Islands, South America and Africa.

During the summer of 1907, at the invitation of General William Palmer of Colorado Springs, Professor Bruner took his family and Messrs. H.S. Smith and R.W. Dawson on a camping trip to that part of the Trinchera estate of General Palmer located on the southern flank of the Sangre de Cristo Range, in northern Costilla County, Colorado. Professor Bruner and his two assistants were to make a survey and report on the biological conditions in this locality and its suitability for a forestry camp for Colorado College. In addition to their general report the party made a list of the birds observed in the region during that summer, which later was published in the magazine Arboriculture (43). They brought back huge collections of insects in all orders from this region, which have yielded many species new to science. During the following two summers Professor Bruner’s insect collections were made mostly in Sioux County and elsewhere in Nebraska. In the meantime, the marriage of H.S. Smith and Professor Bruner’s daughter, Miss Psyche, had taken place, and Mr. Smith had engaged with the Bureau of Entomology in the gypsy moth parasite work in Massachusetts. In 1910 Smith became interested in a land proposition in the Big Horn Valley of Wyoming, and Professor Bruner joined his son-in-law there that summer, making extensive insect collections both in the valley and in the near-by Big Horn Mountains.

In 1911, Professor Bruner decided to discontinue his studies of North American Orthoptera and in the future to concentrate his efforts upon the exotic species of this order. Accordingly, in that summer he disposed of his entire personal collection of North American Orthoptera to Mr. Morgan Hebard of Philadelphia, and it now forms a part of the famous Hebard Orthoptera collection at the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences. The summer of 1912 Professor Bruner and his family spent at Pelican Lake, near Nisswa, Crow Wing County, central Minnesota, again with the result of enriching the Nebraska collection with thousands of insect specimens. In 1913, he made his last foreign trip, this one being to the Orient. He visited Japan and China, but later decided to concentrate his insect collecting to the Philippine Islands. He spent two months at Manila and in the surrounding regions, inspecting the various collections of insects contained in the institutions there, principally the Bureau of Science, Bureau of Agriculture and Agricultural College of the University of Manila, as well as some private insect collections, and giving especial attention to the Orthopteroid insects. A great deal of personal collecting of insects of all kinds was also done by him whnever it was convenient to get into the country for that purpose. Returning to Nebraska in March of 1914, he immediately plunged into the preparation of his Preliminary Catalogue of the Orthopteroid Insects of the Philippine Islands (53), in which the last previous (1895) listing of 289 species of these insects for the Philippines was increased to 733. In this catalogue Professor Bruner present his final ideas on the classification of the Orthopteroid orders of insects.

A well merited but wholly unexpected recognition came to Professor Bruner in 1915. The officials of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition at San Francisco had requested the governor of Nebraska to name “the most distinguished citizen” of the state to receive special honors on Nebraska Day at the Exposition. The then Governor J.H. Morehead appointed a committee of then prominent so the sons representing all parts of the state to name the person to receive this distinction, and this committee named Professor Bruner, who accordingly was fittingly honored at the Exposition.

The last individual who may be included in the honor roll of Professor Bruner’s “boys” is Clarence E. Mickel, who started majoring in systematic entomology under Professor Bruner in 1913, especially with the so-called solitary wasps (Sphecoidea). In 1919, Mr. Mickel Took over the work of Extension Entomologist at Nebraska, resigning in 1920 to continue his graduate work at the University of Minnesota, where he is now Associate Professor of Entomology and has become a world authority on the velvet ants (Mutillidae). Assistant Professor Dawson in 1923 likewise resigned his position at Nebraska to continue graduate work at Minnesota, and likewise is a member of the entomology staff at the institution.

Under the stress of his continued indoor work , Professor Bruner’s physical vigor declined seriously during the school year 1918-1919, and in the spring of 1919 he asked to be relieved of the responsibility of the chairmanship of the Department of Entomology. The then Chancellor of the University, Dr. Samuel Avery, recommended to the Board of Regents that the writer, who had served under Professor Bruner as Laboratory Assistant from 1904 to 1907, Adjunct Professor from 1907 to 1910, Assistant Professor in 1910 and 1911, Associate Professor from 1911 to 1914, and Professor of Economic Entomology from 1915 on, be appointed to take over this responsibility in Professor Bruner’s stead. Along with the chairmanship of the Department, the writer was also appointed to take over Professor Bruner’s work as Experiment Station Entomologist, having helped him in these duties as assistant Station Entomologist from 1907 to 1912 and Associate Station Entomologist from 1912 to 1919, and his work as State Entomologist, having likewise assisted him as Assistant State Entomologist since 1907. Thus relieved entirely of the necessity of being more or less continuously in residence at Lincoln, Professor Bruner returned again to the field work that he so much enjoyed, with the special objective still further to build up the insect collections of the Department.

For The five years preceding his relinquishment of the chairmanship of the Department of Entomology, Professor Bruner had been particularly interested in the insect life of California, Ann had been spending his summers there, collecting large series of insects, as well as some mammals and birds, in that state, particularly in the general neighborhood of Auburn, Placer County, where about 1916, with Mrs. Bruner and his daughter Helen, he had established a cabin in which he lived away from Nebraska. Although in residence at the University as Professor of Entomology during the school years 1919-1920 and 1920-21, and in 1919-20 still teaching the courses in general entomology, Professor Bruner found it necessary to drop out of active service entirely in the spring of 1920 and in much of the school year 1920-21, and to secure a leave of absence for the entire school year 1921-22. The period of his highly active field work may also be said to have terminated with the summer of 1922.

About 1919 Professor Bruner sold his home in Lincoln and from that time forth his real residence was in California, for the most part in Berkeley, two which city the family possessions largely were removed. However, from 1922-23 to 1924-25, inclusive, he was still nominally in residence at Lincoln, living with his sister, Mrs. J.E. Almy, at 2300 A Street. For the following six years (1925-1926 to 1930-31, inclusive), Professor Bruner was absent on leave continuously, and in 1931, he was made Professor of Entomology, Emeritus, by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska. The Golden wedding of the Bruners was celebrated on Christmas Day of 1931. In June of 1933, Professor Bruner presented to the University of Nebraska his complete library on the Orthoptera - the accumulation of a lifetime, totaling 2,591 books and pamphlets - and also his collection of Orthoptera, containing thousands of specimens of this order of insects from all parts of the world, secured by him during a period of sixty years through personal collecting, purchase and exchange. His last active connection with the University was severed upon his retirement from the University Senate on April 29, 1935.

On September 5, 1935, the writer called on Professor and Mrs. Bruner at their home in Berkeley, and talked over “old times” with them. Mrs. Bruner passed away several months later, and it was then very evident that the final departure of Professor Bruner would be delayed but a short time. To Professor and Mrs. Bruner were born three daughters; Psyche (now Mrs. Harry S. Smith) of Riverside, California, Helen M. of Berkeley, California, and Alice, deceased. Surviving Professor Bruner are three sisters, Mrs. Ida M. King and Miss Lily Bruner, both of West Point, and Mrs. John E. Almy of Lincoln. There are three granddaughters - Mrs. Harriet Hansen and Misses Betty and Alice Smith - and three grandsons - Samuel, Lawrence and Richard Smith - all living in California. Professor Bruner’s body was brought to Lincoln for interment in Wyuka Cemetery. At the services at First Plymouth Congregational Church on the afternoon of February 3, 1937, Dr. Addison E. Sheldon, Nebraska’s premier historian, said: “In the future annals of Nebraska, Lawrence Bruner will be known as the state’s first great naturalist. Whatever successors may come in that field his position is secure for all time. His childhood passion was for bugs, butterflies and birds. He was his own teacher for most of his work in this field, like Audubon and Nuttall. The woods, mountains and prairies were his school room. On the honor roll of those daring pioneers who have made Nebraska what she is and what she hopes to be will always be inscribed the name of Lawrence Bruner.”

LITERATURE CITED

1. Aughey, S. First Rept. U.S. Ent. Comm., App., ii, 13-62 (1878).

2. Bruner, L. Can. Ent., viii, 123-125 (July, 1876).

3. Bruner, L. Ibid., ix, 144-145 (Aug., 1877).

4. Bruner, L. Third Rept. U.S. Ent. Comm., 8-64 (1883).

5. Bruner, L. Bull. 2, Div. Ent., U.S.D.A., 7-22 (1883).

6. Bruner, L. Bull. 4, Div. Ent., U.S.D.A., 51-62 (1884).

7. Bruner, L. Can. Ent., xvii, 41-43 (Mar., 1884).

8. Bruner, L. Ibid., xvii, 9-19 (Jan., 1885).

9. Bruner, L. Bull. Washburn Coll. Lab. Nat. Hist., i, 125-139 (1885).

10. Bruner, L. Rept. U.S. Entomologist for 1884, 398-403 (1885).

11. Bruner, L. Bull. Washburn Coll. Lab. Nat. Hist., i, 193-200 (1886).

12. Bruner, L. Rept. U.S. Entomologist for 1885, 303-307 (1886).

13. Bruner, L. Bull. 13, Div. Ent., U.S.D.A., 9-19 and 33-37 (1887).

14. Bruner, L. Rept. U.S. Entomologist for 1887, 164-170 (1888).

15. Bruner, L. Ibid., for 1888, 139-141 (1889).

16. Bruner, L. Bull. 22, Div. Ent., U.S.D.A., 95-106 (1890).

17. Bruner, L. Proc. U.S. Nat. Mus., xii, 47-82 (Feb. 5, 1890).

18. Bruner, L. Bull. 23, Div. Ent., U.S.D.A., 9-18 (1891).

19. Bruner, L. Can. Ent., xxiii, 36-40, 56-59, 70-73 (Feb.-Apr., 1891).

20. Bruner, L. Bull. 26, Div. Ent., U.S.D.A., 9-33 (1892).

21. Bruner, L. Ent. News, iii, 264-265 (Dec., 1892).

22. Bruner, L. Bull. 28, Div. Ent., U.S.D.A., 1-40 (1893).

23. Bruner, L. Bull. 30, Ibid., 34-41 (1893).

24. Bruner, L. Pub. 3, Nebr. Acad. Sci., 19-33 (1893)

25. Bruner, L. Bull. 32, Div. Ent., U.S.D.A., 9-21 (1894).

26. Bruner, L. A Prelim. Introduction to Entomology, 1-322 (1894).

27. Bruner, L. Bull. Lab. Nat. Hist. Univ. Iowa, iii, 58-59 (Mar., 1895).

28. Bruner, L. Rept. Nebr. State Hort. Soc. For 1896, 48-178 (1896).

29. Bruner, L. Bull. 7, n.s., Div. Ent., U.S.D.A., 31-39 (1897).

30. Bruner, L. Rept. Nebr. State Board Agr. for 1896, 105-138 (1897).

31. Bruner, L. First Rept. Merch. Locust Comm., i-x + 1-99 (1899).

32. Bruner, L. Spec. Bull. 3, Dept. Ent. And Orn., U. Of N., 104 (1899).

33. Bruner, L. Second Rept. Merch. Locust Comm., 1-8 (1900).

34. Bruner, L. Bull 38, n.s., Div. Ent., U.S.D.A., 39-61 (1902).

35. Bruner, L. Rept. Nebr. State Board Agr. for 1902, 259-293 (1903).

36. Bruner, L., et al. New Elementary Agriculture, 51-118 (1903).

37. Bruner, L., et. al. Prelim. Review Birds of Nebr. (1904).

38. Bruner, L. Ent. News, xvi, 214-216 (Sept., 1905).

39. Bruner, L. Ibid., xvi, 313-316 (Dec., 1905).

40. Bruner, L. Proc. U.S. Nat. Mus., xxx, 613-694 (June 5, 1906).

41. Bruner, L. Journ. N.U. Ent. Soc., xiv, 135-165 (Sept., 1906).

42. Bruner, L. Ohio Naturalist, vii, 9-13 (Nov., 1906).

43. Bruner, L. Arboriculture, vii, 27-34 (Mar., 1908)

44. Bruner, L. Voeltzkow, Reise Oestaf. Wiss. Er., ii, 623-644 (1910).

45. Bruner, L. Ent. News, xxi, 301-307 (July, 1910).

46. Bruner, L. Ann. Carnegie Mus., vii, 89-143 (Nov. 28, 1910).

47. Bruner, L. Horae Soc. Entom. Rossicae, xxxix, 464-488 (Dec., 1910).

48. Bruner, L. Ann. Carnegie Mus., viii, 5-147 (Dec., 1911).

49. Bruner, L. Proc. U.S. Nat. Mus., xliv, 177-187 (Feb. 11, 1913).

50. Bruner, L. Ann. Carnegie Mus., viii, 5-147 (Dec., 1911)

51. Bruner, L. Proc. U.S. Nat. Mus., xlv, 585-586 (June 11, 1913).

52. Bruner, L. Ann, Carnegie Mus., ix, 284-404 (June 1, 1915).

53. Bruner, L. Univ. Nebr. Studies, xv, 195-281 (Dec. 8, 1915).

54. Bruner, L. Ann Carnegie Mus., x, 344-428 (July 1, 1916).

55. Bruner, L. Proc. Hawaiian Ent. Soc., iii, 149-168 (Sept., 1916).

56. Bruner, L. Ann. Carnegie Mus., xii, 5-91 (Dec. 15, 1919).

57. Bruner, L. Ibid., xii, 92-142 (Dec. 15, 1919).

58. McMillan, C. Bull. 2, Nebr. Agr. Exp. Sta., 1-101 (1888).

59. Osborn, H. Fragments of Entomological History, 220, 300 (1937).

60. Swenk, M.H. Proc. N.O.U., vi, 25-47 (Feb. 27, 1915).

61. Trostler, I.S. Ibid., ii, 17-18 (1901).