Samuel Avery was a professor of agricultural chemistry when asked to serve as Interim Chancellor, Chancellor, and then led the University of Nebraska. Avery was not considered an intellectual and relied on talent within the university to sustain Nebraska’s reputation. Difficult post World War I economic conditions impacted the agricultural economy with falling commodity prices. As a result, budgets tightened and in 1923 students were asked to support the university through tuition contributions.

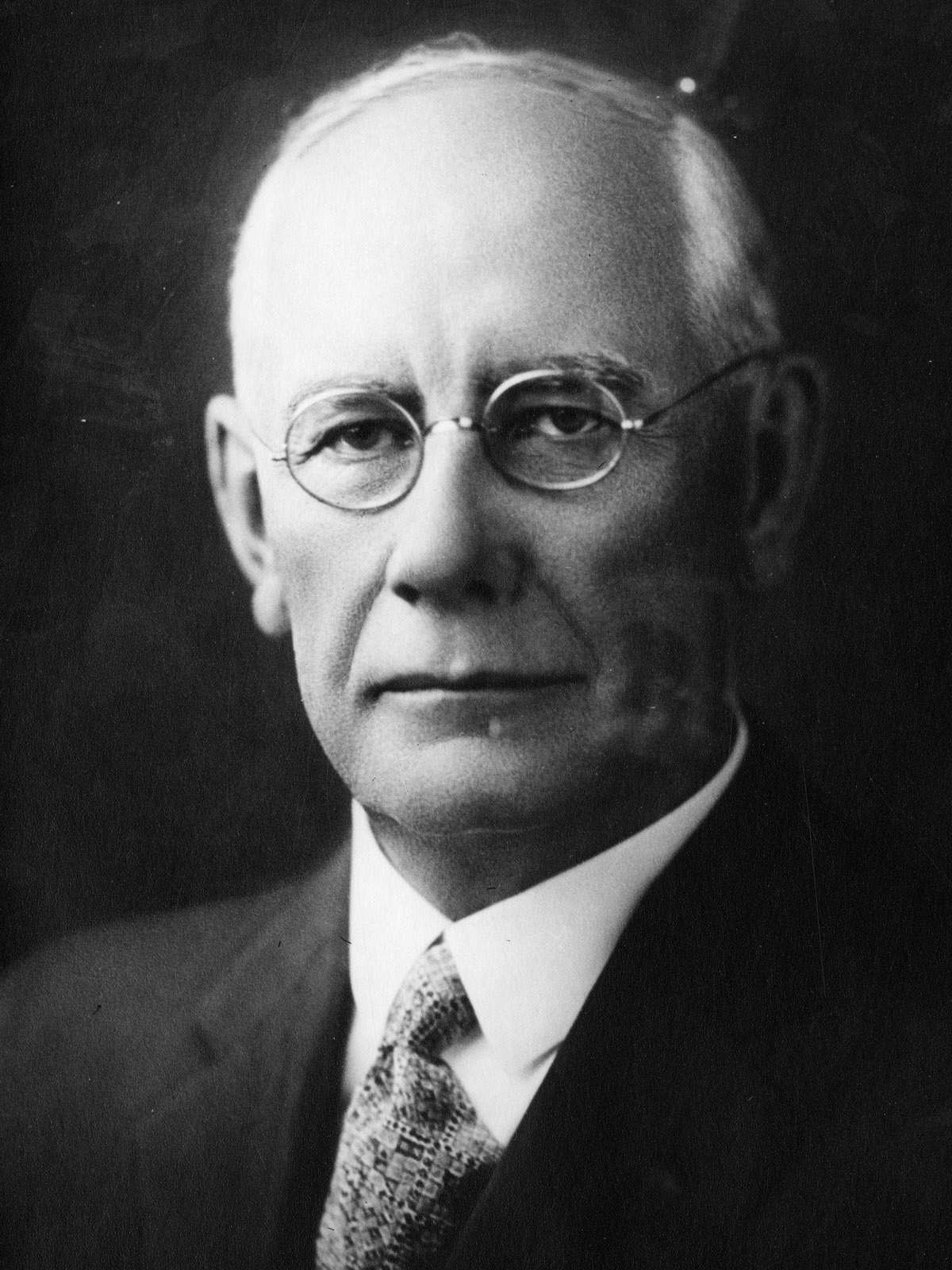

SAMUEL AVERY, AGRICULTURAL CHEMIST

In honoring Samuel Avery today you are honoring your own. For sixty years, barring two, Nebraska was his place of residence. In each of the three main divisions of his life, the preparatory period of youth and young manhood, the precious years of teaching and experimentation in his chosen science, Chemistry, in his long term as University administrator, he had to do with agriculture and agricultural problems. He talked the language of the farmer. It was his own language. His parents and his brothers were lifelong farmers in Nebraska. And no distinction that befell him ever blunted the sharp edge of his appreciation of the circumstances of his origin.

Annals

Samuel Avery was born on a farm near Lamoille, Bureau County, Illinois, April 19, 1865. The Burlington Railroad ran thru the corner of the farm and, of course, his ambition as a child was to be a brakeman. In 1876 the parents and their four boys removed to Crete, Nebraska, living on the edge of Crete and farming the Doane College land. About 1885 the family removed to a farm in Otoe County, near Unadilla, in which county one brother of Samuel Avery, and a niece, still reside.

In the Fall of 1879 Samuel Avery entered the Academy (preparatory school) of Doane College, and he registered in Doane College proper in the Fall of 1882. He graduated therefrom June 23, 1887, with the Bachelor of Arts degree. He took there the traditional course leading to that degree, Greek, Latin, Mathematics, and a smattering of the sciences, his interest in chemistry being already noticeable. He received the honorary degree of L.L.D. from Doane College in 1909, and was a trustee of the College from 1908 to 1925.

In 1887-1888 he was employed for about six months in the lumber yard of Tidball & Fuller at Weeping Water. In the succeeding two years he taught two periods of country school, about six months in each case, one school located two or three miles south of Elmwood, and the other about seven miles northwest of Unadilla. He spent the intervening months during the years from 1887 to 1890 on the farm of his father near Unadilla. “My early days were spent on the farm,” Mr. Avery once wrote, “and until I was 25 I worked on the farm at least each summer, either to make a living or for recreation and health.”

His connection with the University of Nebraska began in the Fall of 1890, when he registered as a special student. In October, 1891 he was given senior standing in the scientific course in the University, specializing in chemistry, at which time, as he later wrote, he “had a ‘pipe dream’ of becoming a sugar chemist”. In 1892 he graduated from the University with the degree of Bachelor of Science. Among his classmates of ’92 were George L. Sheldon, later Governor of Nebraska, Dr. Louise Pound of the faculty of the University, and E.P. Brown, who needs no introduction to this audience.

In the school year 1892-93 Samuel Avery taught Science and Greek in the Beatrice High School, and was senior class sponsor - “greatly beloved by his students and an excellent Science teacher”, being the verdict of his students of that remote time.

In the Fall of 1893 he began work for his Master’s at the University of Nebraska, and was awarded his M.A. degree in 1894, the subject of his thesis being “A Study of Quantitative Electrolytic Methods, with Special Reference to the Determination of Iron, Nickel and Zinc.”

In the school year 1894-95 Mr. Avery was a student at the University of Heidelberg, Germany. At that time the German universities were considered the greatest educational institutions in the world. The years of their humiliation had not yet dawned.

In the Fall of 1895, as an instructor in chemistry, he began his connection with the faculty of the University of Nebraska, a connection which remained unbroken until his death, except for two years when he was at the University of Idaho. In the summer of 1896 he returned to Heidelberg and took his Ph.D. degree there late in that year, whereupon he returned to his teaching at our University, becoming Adjunct Professor of Chemistry in 1897.

August 4, 1897 he was married at Crete to May Bennett, a Nebraska High School teacher, graduate of Doane College, 1891, who had come to Nebraska in 1884, and who honors us with her presence today.

From September, 1899 to August, 1901 Dr. Avery was at the University of Idaho as Professor of Chemistry and Chemist of the Agricultural Experiment Station there.

In 1901 he returned to the University of Nebraska, and for one year was instructor in chemistry on the downtown campus, his title being Professor or Organic and Analytical Chemistry. From 1902 to 1905 he was Professor of Agricultural Chemistry and Chemist at the Nebraska Agricultural Experiment Station. In 1905, upon the resignation of Professor H.H. Nicholson, Dr. Avery returned to the downtown campus as Head Professor of Chemistry, and continued as such till his call to the acting Chancellorship in 1908.

Concerning these early years of his work in chemistry at our University, Dr. Avery wrote in 1915,

“My first permanent work for the University of Nebraska was along the line of agricultural chemistry in the old laboratory at the city campus before the work had been developed at the University Farm. I had the pleasure of organizing the department of agricultural chemistry at the farm and personally completing the investigations on sorghum poisons and methods for the destruction of prairie dogs.”

In 1908 Dr. Avery was made Acting Chancellor of the University, upon the retirement of Chancellor E. Benjamin Andrews. In April, 1909 Dr. Avery became Chancellor, and continued as such until January, 1927, when ill health compelled his resignation. From 1927 until his death, January 25, 1936, he was Chancellor Emeritus and Research Professor of Chemistry at the University. His Chancellorship of the University for a period of 18 years covers one-fourh of the life of the institution. The term of no other Chancellor compares in length with the administration of Chancellor Avery, an administration uninterrupted save for his absence at Washington as a dollar a year man from January to November, 1918, during the first World War, he being a Major in the Chemical War Service, and Vice Chairman of the Chemistry Committee of the National Research Council.

In 1932, in a public address, Dr. Avery referred whimsically to the circumstance of his selection as Chancellor, in the following words:

“when in the fall of ’08 the regents asked me, a wholly inoffensive chemistry professor, to act as chancellor with the special duty of presenting the needs of the university to a legislature elected during a democratic landslide, I found my relations with all of the senators wholly pleasant, even enjoyable. * * * Owing to the influence of the two senators (John E. Miller and E.P. Brown) with some good friends in the House, the University fared better than the regents anticipated and I personally received some credit that I did not wholly deserve. After the legislature had adjourned, I remarked to President Allen of the board of regents that I was now ready and willing to return to the chemical department; to this he replied: “’We want a good man as head of that important department. You have been hobnobbing with the members of the legislature all winter and are spoiled. You are no longer fit to be anything but chancellor.’”

In what was virtually his inaugural address as Chancellor of the University, in the Fall of 1909, Dr. Avery traced the rise and development of agriculture in early historic times.

So much by way of background and chronology.

Avery, Chemist

While Dr. Avery, the scientist, found delight in pursuing the theoretical aspects of chemistry, the class room, the laboratory, constituted for him no ivory tower of escape from the life without. He had, says Dean Burr, a

“practical turn of mind. In the research program at the Experiment Station he always emphasized that we attempt to find the solution to the everyday problems. While he was a real scientist, he was never interested in science for science’s sake, but interested in science for the solution of the problems that confronted the people in their everyday life.”

Such is the testimony of all of Dr. Avery’s colleagues. Dr. F.J. Always, now at the University of Minnesota, succeeded Samuel Avery in 1905 as chemist at the Nebraska Agricultural Experiment Station. Of Avery’s work in chemistry at Idaho, and later at Nebraska, Dr. Always says that, at Idaho,

“All the time that he could spare from his classes, he devoted to the work of the experiment station, analyzing soils, waters, feeding stuffs, wheat and other Idaho produced foods and carrying on experiments in sugar beet production. At that time there was a widespread opinion in Idaho that the Paris Green being sold there was commonly adulterated and that such an adulteration accounted for the unsatisfactory results secured by many of the horticulturists. Dr. Avery secured as many samples of Paris Green as possible from dealers in different parts of the state. * * * Then he undertook a thorough investigation of the composition and properties of Paris Green and other arsenical insecticides and became an authority on this subject, being appointed the referee on insecticides for the American Association of Official Agricultural Chemists.”

He completed his study of arsenical insecticides upon his return to Nebraska. Dr. Always further states that while Avery was at the Nebraska Agricultural campus,

“He carried out, along with many routine duties as a chemist, investigation into the cause of sorghum poisoning of cattle, finding that his was due to the presence of glucoside of hydrocyanic acid which, in the stomachs of the cattle, liberated the very poisonous hydrocyanic acid.”

This finding, as pointed out by Professor Alvin Kezer, Chief Agronomist of Colorado State College, a former student in Dr. Avery’s Experiment Station Laboratory, “was contemporaneous with the discovery of the same principle by two English chemists working in Egypt.” Dr. Always proceeds:

“Among the other problems to which he devoted attention there may be mentioned corn stalk disease, eradication of prairie dog colonies, improvement of insecticides used by Nebraska horticulturists and, in cooperation with the late Dr. T. L. Lyon, the improvement of the quality of Nebraska grown wheats. Through this period he continued to act as referee on insecticides for the Association of Agricultural Chemists.”

Prussic acid in sorghum and kaffir corn, extermination of prairie dogs, arsenical insecticides, sulphur and lime in cattle dips, constitution of Paris Green and its homologues, are some of the lines of Dr. Avery’s research, as listed in “American Men of Science”.

Probably the greatest single contribution of Samuel Avery, the chemist, to the farmers and millers of Nebraska, was in connection with the “bleached flour case”. I quote from Dr. Filley’s memorandum:

“Spring wheat was an important crop in Nebraska during the years when the state was first settled. Unfortunately the yield was low. Turkey Red wheat was brought to Nebraska by Mennonite immigrants, but was not widely grown until it was promoted by the Experiment Station. Unfortunately for Nebraska wheat producers, the flour that was made from Turkey Red Wheat in the early years had a slight ivory tint and did not meet the requirements of the American housewife, who apparently believes that the quality of bread is determined in part by lack of color. The western millers soon worked out a process to bleach the flour. Then the Federal Government stepped into the picture and demanded that the sacks containing the flour be labeled “bleached”. The label reduced the demand for the flour and it could be sold only at a reduced price.

“The chemist at the Nebraska Experiment Station, Dr. Samuel Avery, undertook to determine the extent to which bleaching changed the food value of the of the flour. He eventually announced that ‘the minute traces of yellow color present in flour can be bleached with such minute amounts of nitrogen peroxide that it is difficult to determine any effect on the flour other than the bleaching and the presence of nitrites’.

“Before the ‘bleached flour’ case came up for trial in Kansas City, Dr. Avery had been promoted and his assistant Dr. F.J. Alway, had become station ‘chemist’. The trial lasted for four weeks. Dr. Always was the last witness called and occupied the stand for about a day. His main work during the trial was in advising the attorneys for the millers as to the questions to ask the witnesses for the Government. As a result of the work of Dr. Avery and Dr. Always, the millers won the case.

“As a result of the decision the labeling of the bleached flour was no longer necessary and the price discrimination against Tureky Red Hard winter wheat was at an end. If the price of Nebraska grown wheat was raised five cents per bushel by this decision, and this seems to be a very reasonable assumption, the farmers of Nebraska have received an average annual increase in income, as a result of this one experience station project, of more than $2,500,000 per year from 1910 to 1940.”

In an address of welcome to a Farmers Institute Conference near the outset of his Chancellorship, Dr. Avery summarized the agencies of advancement in the agricultural field, with modest and pleasant allusion to his own participation therein, as follows:

“The agricultural advancement has been largely due to three forces: the agricultural experiment station which has supplied information; the agricultural schools and colleges which have developed trained young men to man the positions in the experiment stations; and finally the farmers institutes which have brought the knowledge obtained to the immediate attention of the farmers. These three agencies have worked hand in hand. Whatever has been for the good of one has been for the good of the other. Their united, harmonious action has been conducive to the agricultural solidarity that prevails. The agricultural advancement due to the Farmers Institute has not been brought about without some personal hardships. It is a pleasure to me to address you this morning as I know from personal experience what some of these are, as I have personally spoken on the institute platform from the Panhandle to the capital of Idaho, and from Callaway to Nebraska City of this state. It was not entirely a succession of Pullmans and first class hotels. I remember very distinctly in Idaho when arriving at a town to hold an institute, we were informed that the regular hotel was closed down for renovation and must go to a second class lodging place. Imagining that my room was a little close in the night I reached out, raised the sash and thrust a pocket knife under it, in order to acquire a little ventilation. It did seem a little cold that night with the wind blowing as it did across those sage brush plains but I had the satisfaction of feeling sure that I had air enough to breath. In the morning I discovered, somewhat to my surprise, that I had raised an empty window sash. But after all, the strenuous work of bumping along on freight trains during the night in order to have the privilege of speaking three times the next day, and the various other things institute workers encountered, are fully matched by the efforts of the local managers.”

Avery, Chancellor

Time does not avail to speak of Samuel Avery, the Chancellor as fully as one should. His selection as Chancellor was a pivotal point in his career, but it made no difference in the man himself. The arrogance too often exemplified by those in public office never fell as a mantle about his shoulders. He was the same Avery, called to a wider sphere of usefulness, to serve the people of the State no longer as the head of a department but as the head of the whole University, remaining as before kindly, a man of quiet humor, simple in manner, modest, interested as of old in his science and in its contributions to the farmer, and in the College of Agriculture and the Experiment Station through which the University channels its service to the broad fields of Nebraska. He had been faithful over the relatively few things entrusted to his care. Thenceforth his jurisdiction as Chancellor was over the many.

I leave to others more competent than myself, thru close association, to characterize Avery’s work as the chief executive of the University of Nebraska. Charles S. Allen, of the class of 1886, was a regent of the University for two terms, and his removal to California some 30 years ago was a great loss to Nebraska. He was one of the regents who participated in the selection of Dr. Avery as Chancellor. Mr. Allen says of him:

“As an administrator he had ability of a high order. In a state university it is necessary to keep the institution in touch with the people and make them feel it is being managed for their welfare. Sam knew the people of Nebraska was one of them and in sympathy with them. The people knew this, felt the institution was ministering to their needs and gave him loyal support.

“Many personal problems arise in the life of a university requiring tact to solve them. Avery had unusual capacity to handle these. One requirement is a desire to be impartial, fair, and to make this clear to the parties concerned. Another is to sense true situations, the motives and interests involved, and use the right approach toward any controversy actual or potential. Avery was always candid and fair and he had an uncanny knowledge of the human element which makes so much trouble in the affairs of life.

“Realism, - a keen sense of the actual world of action - and sound judgment, are indispensable qualities in the administration of public institutions. Avery had these qualifications.

“My association with him both as regent and personal friend are among the memories of the past, to recall which is a pleasure.”

E.P. Brown of Arbor Farm, who, as a farmer, as legislator, as regent, was uniquely qualified to know Avery, the Chancellor, analyzes his administration as follows:

“My idea about Sam is that he made his mark because he had and KEPT a simple view of life and especially of the great problems he had to meet and solve. As you know he in his personal habits liked the simple things and it was his nature and his way to apply this liking to his public and his professional problems. As solution is almost never found wholly on the side of plaintiff or defendant, Sam’s single-minded search for the simple truth inevitably brought him the ill will of both partizans. He suffered in his own phrase, ‘the fate of all neutrals, the enmity of both combatants’. There is of course, a neutrality that is not to be distinguished from cowardice and that often impels a man to be the loudest and most violent of partizans. This was not Avery’s. His loyalty was simply to the University and not to any faction which proposed or opposed any given line of policy.

“The best illustration is the great removal fight. His private and personal view of that question was that of the Antis. But his official view was that if the Pros. would secure or could obtain funds to remove, the University would be better served than if it stayed put and was starved for revenues. So the Pros. were encouraged to demand, and helped to secure, a greater increase in appropriations than had ever been thought possible for the University. This turned out to be the thing that prevented removal (the great cost). But an atmosphere had developed which made it possible to get for the school on its old and historic situs the funds which permitted the great material development of the 20’s. Sam’s loyalty was simply to the institution itself. His greatness appears in the way the hot zeal of both factions was used in the end, greatly to serve her. For a time he was the best hated man the University ever had. He foresaw this and suffered from it, for like most plain men he liked the esteem of his fellows. The event has fully vindicated his wisdom and justified his policy. I am glad that before he died this had been generally admitted by most of those who had been most bitter in opposition.

“Sam by nature and environment had a farmer’s mind - a Nebraska farmer’s mind. * * * In Nebraska legislatures, predominantly agricultural, his influence was great. Many times I have known appropriation committees after they had heard both sides in the matter of University revenues, to defer their decision until they had has opinion. He usually got less than the rapid old grads demanded - he always got more than the Scotch economizers liked. I know about these things because I was for some time his spokesman in both House and Senate and at all times honored by his confidence and friendship. It is not by accident that the Golden Age of the University was in Sam’s time as Chancellor.

“Avery never to my knowledge, allowed provocation, however violent, to goad him into public utterance though his sense of undeserved abuse was deep and hot. He had a lot of temper which he always kept. Base enough in itself for a big monument.”

Dean Burr emphasized the practical quality of Chancellor Avery’s mind, his approach to problems from every angle before taking action, his sense of thrift and economy, making the money spent by the University give the greatest return.

The chapter on the growth of the University, on all of its campuses, during the years of Avery’s Chancellorship has yet to be written. In the columns of the Nebraska Farmer in 1915, Dr. Avery tells us of things done in the College of Agriculture in the first six years of his Chancellorship, with the co-operation of legislators, regents, deans and professors. He says:

“Six years ago there were ten professors in agricultural subjects and four instructors. There are now thirty-four professors and sixteen instructors. This is, more than three times as many persons are now giving instruction in agricultural subjects in the university as at the beginning of 1909.

“Up to six years ago the college of agriculture, which was organized in the early days, had been submerged in the industrial college. In the session of the legislature of 1909 a bill, drawn under my direction and introduced and pushed by Representative Otto Kotouc of Richardson County, was passed that reorganized the university and named the college of agriculture as one of its colleges.

“The school of agriculture as a part of the industrial college had long been in existence. In 1909 there were 348 students in the six months’ course. The latest complete record shows an enrollment of 515. The number of students registered in the college of agriculture in the first year of its separation from the industrial college was 23. In the past year the registration was 468.”

Prior to 1909, we are told, the University of Nebraska granted a total of 3,674 degrees, and in the 10 years following 1909, a total of 4,124 degrees!

As noted in the Semi-Centennial Anniversary Book of the University, put out in 1919, the value of important buildings erected on the City campus from 1909 to 1919 was $898,000, and on the Farm campus $512,510, and on the Omaha campus $372,300. In that period, the estimated value of University buildings on the City campus rose from a total of $685,000 to $1,561,000, and on the Farm campus from a total of $213,500 to $704,280.

It is trite to observe that brick and mortar, without more, do not make an educational institution. But it would be illuminating to place pictures of the three campuses of the University, Agricultural College, downtown, Omaha, as there were in 1908 when Avery became Acting Chancellor, alongside pictures of the same campuses in 1927, when his chancellorship ended. The fifteen years since then have been grueling, and it has not been possible for the State to add much in that period to the physical plant of the University. Standing today on the campus where we are met, or on the downtown campus, or on the Omaha campus, and considering all of the results and the influence, tangible and intangible, that were wrought into the fiber of the University under his administration, we may well say of Avery - as of Sir Christopher Wren in St. Paul’s in London - “If you seek his monument, look about you.”

The years of Avery’s Chancellorship were tumultuous years. Growth of itself spells much of disarrangement and upheaval. There were the years when the removal fight within the University was coming to its crisis, and tensions were engendered that time has buried in the debris of the past. There were the war years, when academic freedom was under assault, and high emotion was at a premium, resulting in June, 1918, in the trial of the University Professors before the Regents. There were the boom years following the first World War, and there was the period of economic distress which, in Nebraska, long antedated 1929. The routine stresses of University administration, the high tides that swept the State of Nebraska and its people, reacting necessarily upon their principal educational institution, all found a focus on the desk of Chancellor Avery. No wonder that from such pressure of work and responsibility Avery, the man, had to find escape at intervals, as when, in the late winter of 1912, he spent three days on one of the seed corn specials and talked to the farmers at nearly every point where the train stopped. No wonder that he turned aside momentarily from the day’s work, when the destruction of the old main building on the downtown campus was in contemplation, to tell a caller about the old grad. who besought him, “Don’t tear down that building. I met my wife there”! and of the other who implored him, “Tear it down! I met my wife there”.

Autumn

But time and hard labor are exacting millers and they take their toll. In January, 1927 ill health compelled the resignation of Chancellor Avery, and he entered upon the period of his retirement. After a trip to the West Coast for the betterment of his physical condition, he returned to Lincoln and re-entered the chemical laboratory. Avery, the scientist, was home again. We may well imagine his delight at turning once more to chemical materials, whose reactions were to him far more predictable than those of individuals or of the public. I remember hearing at the time of his pleasure at getting back, as it was phrased to me, “to his smelly old laboratory.”

We are afforded a glimpse of him there, thru the eyes of his colleagues, Dr. B.C. Hendricks and Dean Fred W. Upson. Dr. Hendricks says that Avery, upon his return to the laboratory,

“started a piece of research almost where he had dropped it when he took up the chancellorship. And it was not mere self entertainment that he indulged in! Within a year he had results that were accepted for publication in one of our chemical journals. And other work followed in healthy amounts. * * * He was able during the years he worked as Research Professor Emeritus not only to add to the solution of theoretical problems but he in a more than usual degree added to the mechanical proficiency of the research in which he was engaged. * * * He had, after a year or two, built up one of the best combustion analysis laboratories to be found in any university in the middle west.”

Writing in a chemical journal in 1930, Dean Upson says of Avery that

“When Doctor Avery came back to the chemical laboratory in the fall of 1927 after serving the University of Nebraska as its chancellor for nearly twenty years, he resumed work in synthetic organic chemistry almost where he had left it in the fall of 1908; it was as if he simply had returned to the laboratory after a short vacation. In no time at all steam baths were bubbling, filter pumps were pumping, distilling apparatus was distilling, and Doctor Avery was making new compounds.”

In a recent letter Dean Upson gives expression to this tribute to Avery:

“After he retired and had a laboratory of his own in the chemistry department, the way he always deferred to me as head of the department was at times really embarrassing. He was a perfectly delightful person to have around and took special pains to identify himself with the department and made every effort to fit in just as one of us and in no way either by deed or implication made use of his position as Chancellor Emeritus. He preferred to be known as Research Professor of Chemistry.”

What more delightful and inspiring experience for the chemistry students of that day than to have this association in the laboratory and in occasional conversation with Avery, the scholar, Avery, the widely known administrator, Avery, the sage!

It was my privilege to meet him at intervals in the last years of his autumn, crowning nearly a half century of our mutual friendship, to note the shrewdness and kindliness of his appraisal of men and measures, his meticulous care and accuracy in the handling of his affairs, his considerateness toward the debtor who could not pay per contract, occasional flashes of his quiet humor - the Avery of the period of fruition, seasoned in judgment, mellowed by years of toil and observation, who through a long lifetime had assorted true values from the meretricious, and who now faced forward unafraid. He was not one who wore his heart upon his sleeve, was not given to much speaking, and when he sent me in his own hand a brief business letter, in early January, 1936, when six months of the period of his last illness had elapsed, and for the first time wrote beneath the familiar signature “S. Avery”, the words “Classmate and friend”, I knew, and I know that he knew, that he was saying thereby, “Farewell”.

The visitor to his grave in Wyuka Cemetery, at Lincoln, will find, appropriately, a headstone flush with the earth, eloquent in its brevity - “Samuel Avery 1865-1936”.

I always feel a bit sorry for those who have not spent their youth, at least, in the country. It may be the life in the open, it may be something inherent in the very nature of their occupation, but there are no more sterling individuals or citizens than the finer type of country folk. When you return to your home and gather to the evening lamp, look about you. It may be that within your own family circle you are raising up some Samuel Avery of the days to come, who shall perform fine service and rise to high position in the commonwealth, who shall bear his honors in kindliness and simplicity of spirit, never losing contact with the ranks from which he came, who shall pass on with the “Well done!” of his contemporaries and of all who shall enter into his labors.

(Address by T.F.A. Williams at Student Activities Building, Agricultural College Campus, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, February 4, 1942, on the unveiling of the portrait of SAMUEL AVERY in the Nebraska Hall of Agricultural Achievement)