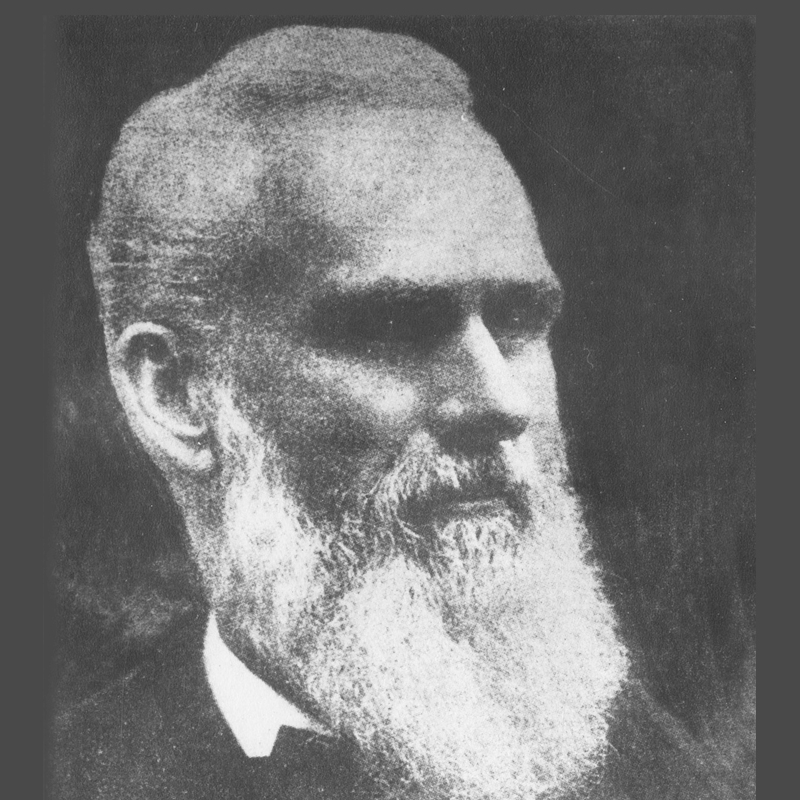

Samuel R. Thompson was the first professor of agriculture and the first dean of the College of Agriculture at the University of Nebraska.

SAMUEL R. THOMPSON, FATHER OF THE AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE

We gather this morning to honor an educational pioneer of fifty years ago - Samuel R. Thompson, first professor agriculture, first dean, and father of the Agricultural College of the University of Nebraska. To Professor Thompson was handed the task of creating an agricultural college, where no such college had ever before existed, and indeed when there was hardly a model on which to build. He was the founder of the Nebraska Weather Service, the early promoter of the sugar beet industry and the father of agricultural extension in Nebraska.

Let us, for a moment, learn something of the man. He was born in Crawford County, Pennsylvania, April 17, 1833 - nearly a hundred years ago. He graduated from Westminster College at the age of thirty years. Before graduation he had been in public school work and following graduation, he was professor of natural sciences in the Edinboro State Normal School for two years. Later he was engaged in high school work at Pottsville, Pa., and then went to Marshall College, Cabell County, West Virginia, and reorganized it as a state normal school.

His first official connection with the College of Agriculture of the University of Nebraska came on September 5, 1871, when we find in the regents’ reports this notation: “S.R. Thompson was elected to the Chair of Theory and Practice of Agriculture, but not to enter on his duties sooner that one year from the present.” On June 25, 1872, the Agricultural College was formally established and ordered to be opened and Mr. Thompson appears to have begun his duties that fall.

Professor Thompson resigned from his position at the Agricultural College in 1875. For a year he was principal of the Peru Normal and served as state superintendent of public instruction in Nebraska from 1877 to 1881. He also filled out the term of Professor W.W.W. Jones as superintendent of the Lincoln city schools when Mr. Jones succeeded him as state superintendent. Later he again assumed the professorship at the Agricultural College and from that he was called to the professorship of physics at Westminster College in June 1884. Professor Thompson passed away October 28, 1896.

When Professor Thompson arrived to take up his work at the University of Nebraska, he was confronted with a set of conditions both different and yet similar to those of today. Throughout his years in Nebraska, he was confronted with the problem of interesting people in an agricultural education, a situation that exists to a certain extent today. But if we consider our own task difficult, what must have been the troubles of Professor Thompson and Chancellor Benton in launching an agricultural college, when most people did not want an agricultural college and often were not at all backward in saying so?

Let us picture for a moment the College of Agriculture in the days of Professor Thompson. Many people do not know that a College of Agriculture actually existed some fifty years ago. They very politely tell us that the College of Agriculture came into existence in 1909, and that prior to that time the agricultural instruction of the University was given in connection with the Industrial College. But they are mistaken. A College of Agriculture existed prior to the establishment of the Industrial College in 1877, being merged into the Industrial College at that time.

But it must be admitted that one of the reasons for the establishment of the College of Agriculture was the necessity implied in the Federal Land Grant Act requiring such instruction. To those of academic mind a College of Agriculture appeared to be more or less a necessary evil, while to the actual farmer “book farming” seemed worse than useless. Bear in mind that there were few agricultural colleges in the United States at this time and none of them probably could be said to be firmly established. With no precedent to follow, little support from either educators or farmers, we may well ask what we would have done had we been placed in the shoes of Professor Thompson. And yet, looking backward fifty years, we see that Professor Thompson and Chancellor Benton in those first three or four years sensed the three great missions of the agricultural college and had begun work in the three major lines followed today, instruction, experimentation, and extension.

Remember that in those days there was no plant and no equipment with which to work, as we think of plant and equipment today. When Professor Thompson took up his duties at Nebraska, the University had not yet come into possession of the present college farm. For some time, it was evidently the idea that some of the land forming the endowment of the University or belonging to the state could be utilized as the model farm, and in fact, for a while the University did make use of land lying in the vicinity of the fairgrounds. It was not until September 1, 1874, that the University came into possession of the present agricultural college farm, and even at that, it was just a country farm. It was not until nearly a quarter of a century later that any of the buildings standing today were erected.

Book farming was looked down upon by the cultured scholars of the uptown campus and by the farmers of the state as well. There were no students in agriculture the first three years that the college was open. But in 1874-75 fifteen students enrolled, this unusual attendance being due to the fact that the University had come into possession of the present college farm and could offer board and room at an economical figure and furnish the students with remunerative employment as well.

But Professor Thompson was not idle. We often think of agricultural experimentation as having originated with the passage of the Hatch Act of 1887 and of agricultural extension as having originated with the passage of the Smith-Lever Act of 1914 or certainly not earlier than the 90’s when farmers’ institutes were in vogue. But Chancellor Benton and Professor Thompson were busy with both of the matters before there were any students taking agricultural courses.

We must remember that when agricultural colleges came into existence friends and critics were not just sure what these colleges were supposed to accomplish. Professor Thompson raised this question in 1873:

“In planning our future work in the Agricultural College, the first question to be settled is, shall we aim to present a model farm, beautiful in its location, harmonious in its arrangements, exact in its divisions, neat in its keeping, and profitable in its working, or shall we arrange for an experimental farm, where it shall be our main business to discover new agricultural truth, rather than to exhibit what is old. The model farm will make the best showing to the general public and will incur less expense, but in the long run the latter will be of more real service to the state.”

It is thus pleasing to note that even fifty years ago Professor Thompson thus forecasted and laid the foundations of agricultural experimentation. Even before the college had come into possession of the present farm and when it was making use of some of the land composing the original land grants, Professor Thompson was busy with his experimental work. Sugar beets appear to have been one of his hobbies and in 1873 he took it upon himself to promote the industry within the state by distributing beet seed to farmers. Even though the results achieved from distributing the sugar beet seed were not all that were to be expected, Professor Thompson believed that ultimately success would greet the experiment. He began making experiments in growing different varieties of oats and wheat and succeeded in selling his wheat at fifteen cents a bushel above the market price.

Turn to another side of his work and we find Professor Thompson conducting farmers’ institutes in various parts of eastern Nebraska. When people would not come to the College of Agriculture, Chancellor Benton and Professor Thompson hit upon the plan of carrying agricultural education to the people. In the recommendations of Chancellor Benton, we even find the suggestion of holding the first meetings of Organized Agriculture, such as we are attending this week, though it is not apparent as to whether it was immediately carried out. During the winter of 1873-74 four farmers’ institutes here held. So great was the attendance than at one of the institutes there was not even standing room.

How modern, for instance, do the following recommendations of Professor Thompson sound:

“We should not solely seek to discover new agricultural truth and to fit young men for illustrating its value in the community, but we should make a special effort to disseminate agricultural knowledge through the community. This we may do in several ways, as by publication of reports, and through the press, and by the public lectures of our teachers. There seems to be no good reason why the teaching of our professors should be confined entirely to the classroom. The great public who support the University are certainly entitled to receive a share of the instruction the University may have to impart. If only knowledge is spread abroad and improvement stimulated, what matters it, whether all be done in the conventional way or not?”

When one thinks of Professor Thompson, he thinks of a scholar of the old school. In this day of peppy youngsters who do the teaching, of rules and regulations, it is worthwhile to come upon such a figure as that of Professor Thompson, even if only in retrospect. “Professor Thompson was tall, of pleasant manner and with a scholarly bearing,” Dr. Bessey stated. “In his later years, his white hair and full beard of almost snowy whiteness gave him a venerable look. A kind face from which looked out the clear soft eyes which betokened the sympathetic friend, completes the picture of the man who has gone from us.”

And this also from Dr. Bessey:

“We need not go back to those early days and criticize the work of those who were compelled to make educational bricks without straw, and while we may readily admit that mistakes were made, we should none the less honor those who toiled and planned. Time has shown that those who once criticized Professor Thompson’s work were themselves as far as he from having the true solution of the problems of that time. As we look back to those days of small things, those days in which the beginnings were made, we are led to honor the man who shrank not from the labor which was laid upon him. As I look over the country and compare the work done by Professor Thompson in this young University, with that accomplished by men in similar positions in other institutions I am constrained to say that Nebraska was very fortunate in having the services of so cultured a man.”

What are the lessons for us today in a brief biographical sketch such as this? Perhaps, like many critics, we are prone to make fun of the absurdities and forget the real accomplishments. But is it not a striking commentary on the wisdom of these early men that in the last fifty years we have not been able to add a single basic principle to those originally established of instruction, experimentation, and extension?